Other Risk Benefits

Group Term Life Insurance Benefits:

Group Dependent Life Insurance Benefits:

Supplemental Life Insurance Benefits for Employees and Dependents:

Group Accidental Death and Dismemberment Plans (AD&D):

Long-Term Care Plans:

Group Travel Accident Insurance:

Tax Implications of Other Risk Benefit Plans:

Group Life Insurance Programs

Introduction:

The Distinctive Benefits:

Financing Considerations:

Plan Provisions Unveiled:

Enhancing Plan Flexibility with Additional Provisions:

Group Dependent Life Insurance

As previously indicated, most group life insurance plans have provisions covering the insured’s dependents. Under such plans, a dependent is defined as the insured’s spouse (who is not legally separated from the insured). Dependent children are usually defined as unmarried children, including stepchildren and adopted children, between 14 years of age and some predetermined limit, usually between the ages of 19 to 21. The age limit may be extended to 25 if the child is a full-time student. Generally speaking, different coverage levels are offered for spouses versus dependent children. A plan will permit greater levels of dependent coverage only if they are fully paid by the employee. Under such provisions, death benefits are paid in a lump sum to the employee or, if deceased, the employee’s estate.

The amount of coverage for a dependent’s life is usually minimal. Any coverage over $2,000, when the employee pays premiums, may be subject to federal taxes. Adverse tax consequences might not apply if the employee pays the premiums. Occasionally, coverage amounts are lower until a dependent child reaches a certain age.

Normally, a single premium is applicable for all participating employees and is unrelated to the number of a given employee’s dependents. In some plans, premiums vary based on the age of the employee, but most premiums are uniform.

Group dependent life insurance usually carries a conversion privilege, but this privilege might only apply to spousal coverage. However, some states mandate that this privilege apply to all covered employees.

Supplemental Life Insurance

Numerous companies empower their employees to acquire supplemental life insurance through the same provider offering basic coverage, facilitated by the convenience of payroll deduction. This unique feature seamlessly integrates elements of both group and individual life insurance policies, often manifesting as a group universal life plan. Typically, obtaining coverage involves minimal individual underwriting, influenced by competitive factors and the number of employees enrolled in the company's insurance program. Notably, since this supplemental coverage is individually owned rather than company-owned, it remains with the employee even in the event of termination.

Within the framework of most group life insurance plans, participants have the option to augment their coverage with this additional layer, leaving the employer responsible solely for basic coverage. This contributory supplemental coverage can be seamlessly integrated into the basic plan or structured independently. Occasionally, companies may restrict access to supplemental coverage, confining it to a specific subset of employees.

The extent of supplemental coverage within such plans is meticulously outlined in the benefit schedule. Some plans mandate full coverage, while others offer the flexibility to opt for partial coverage. Yet, the choices made by employees in these plans introduce the potential challenge of adverse selection, necessitating stringent underwriting rules. Insurance companies typically demand evidence of insurability before underwriting full coverage. However, in the case of a sufficiently large group, insurers may waive the need for evidence of insurability for basic coverage. Any additional coverage amounts, though, remain contingent on evidence of insurability and undergo individualized underwriting assessments.

Accidental Death and Dismemberment Plans

Integrated into group life insurance benefit programs, Accidental Death and Dismemberment (AD&D) features enhance coverage by providing additional benefits in the unfortunate events of accidental death or specified injuries. Typically, these plans operate on a contributory basis, and the fundamental group AD&D coverage is commonly incorporated as a rider to the group life insurance plan.

Alternatively, employers have the option to procure distinct contracts outside the purview of a group life insurance policy, known as carve-out plans. These plans, often more cost-effective, serve to furnish employees with broader and tax-favored benefits.

In the conventional framework of AD&D insurance, individuals eligible for group life insurance automatically gain access to this supplementary coverage, provided the employer includes it in the plan, and the insurance company incorporates it into the original contract. These plans may have a probationary period, typically spanning three to six months, before AD&D coverage becomes accessible.

The benefits offered by AD&D coverage are usually double the amount of the group term life coverage. This payout is triggered only in the case of accidental death or bodily harm, encompassing the dismemberment component. Insurance providers commonly specify a timeframe within which the covered individual must pass away after an accident to qualify for the benefits.

The definition of the terms used in the table are given below:

• Quadriplegia: If an accident causes total paralysis of both upper and lower limbs, and the accident results in a covered loss, 100% of the AD&D insurance benefit is payable.

• Hemiplegia: If there is an accident which causes total paralysis of the upper and lower limb on the same side of the body, and the accident results in a covered loss, 50% of the AD&D insurance benefit is payable.

• Paraplegia: If the accident causes total paralysis of both lower limbs, and the accident results in a covered loss, 75% of the AD&D insurance benefit is payable.

• Reattachment of hand or foot: If an accident results in a covered loss of hand or foot, even if it has been surgically reattached, the insurance company will pay 50% of AD&D insurance benefit payable.

Enhanced Benefits during Business Travel

In the unfortunate event of an accident occurring during an employee's business trip, elevated benefits are often accessible. Further insights into these augmented provisions can be gleaned in the subsequent sections covering group travel accident insurance.

Under an Accidental Death and Dismemberment (AD&D) plan, death benefits are disbursed to the employee's designated beneficiary, as specified in the group term life insurance plan. Conversely, benefits related to the dismemberment segment are directed to the employee. Comprehensive coverage is extended to both occupational and nonoccupational accidents.

Upon retirement, the majority of employee plans cease coverage, and conversion privileges are typically rescinded due to the associated high costs, influenced by the retiree's age. While some employers choose to extend coverage to retired employees, the coverage is often scaled down, commonly by 50%.

Group Disability Benefits

Group disability benefits are meticulously crafted to safeguard a covered employee's income in the face of accidents or illnesses. Statistical data underscores the relevance of such coverage, revealing that approximately one-third of employees may encounter a disability lasting at least 90 days, with one-tenth facing the prospect of permanent disability. In recognition of these risks, a significant number of employers incorporate group disability protection into their benefits offerings.

A short-term disability program, typically providing benefits for up to six months. Funding for these plans is derived from a combination of insured and uninsured sick-leave plans.

A long-term disability program is strategically crafted to furnish extended disability benefits, potentially spanning the entirety of an employee's life.

However, a notable challenge inherent in disability programs is the intricacy of coordinating benefits across diverse plans, encompassing both private and government-sponsored initiatives. It's crucial to acknowledge that disability benefits are not exclusive to workplace programs; they are also accessible through Social Security and various other government initiatives. The coordination of benefits extends its reach to include uninsured paid-sick-leave plans and employer-sponsored retirement plans. This coordination holds significant importance as, without it, an employee may find themselves receiving payments from multiple sources, yet encountering potential gaps in compensation during transitional periods between one plan and the next. Careful consideration of this coordination is pivotal to ensuring a seamless and comprehensive support system for the employee.

Sick-Leave Plans: Ensuring Income Continuity

Insured Disability Programs: Balancing Coverage and Control

Exclusions in Disability Programs: Clarifying Coverage Parameters

Within the constructs of these programs, certain exclusions are explicitly outlined in their contracts to define the scope of coverage. Noteworthy exclusions include:

• No benefit is payable if the employee is not under the care of a physician.

• No benefit is extended in cases where the disability stems from self-inflicted injury.

• No benefit is provided if the employee engages in compensated work during the disability term.

For long-term plans, additional exclusions may apply:

• No benefit is awarded in the event of war, whether declared or undeclared.

• No benefit is granted if the disability arises from the commission of a crime or felony.

• No benefit is disbursed for disabilities resulting from mental illness, alcoholism, or drug addiction.

Except for pregnancy, pre existing conditions may also be subject to exclusion. The explicit exclusion of pregnancy aligns with legal provisions such as the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. This exclusion might encompass any disability initiated within the initial 12 months of coverage if the employee was undergoing treatment before eligibility or within 90 consecutive days preceding the onset of the disability period. These exclusions serve to delineate the boundaries of coverage, ensuring clarity for both employers and employees within the framework of disability benefit programs.

Benefit Schedules for Disability Programs: Striking the Right Balance

Crafting a benefit schedule for disability programs involves expressing the benefits in a format such as a flat dollar amount, variable amounts by classification, or as a percentage of an employee's earnings.

The primary challenge in designing such a schedule lies in finding the delicate equilibrium where the compensation is sufficient to support the disabled employee but doesn't disincentivize their motivation for rehabilitation and a return to work. Achieving this balance entails a thorough examination of the relationship between an employee's pre-disability earnings and potential disability earnings. Whether using a percentage or flat amount, the typical target result hovers between 50% and 70% of the employee's pre-disability gross income.

Many plans derive disability benefits from a percentage of regular earnings, spanning from 50% to a full 100%. The higher end of this spectrum risks diminishing the employee's incentive to return to work, as the net earnings, with lower taxes and reduced work-related expenses, may provide sufficient comfort. Earnings considered often include bonuses, overtime, commissions, and other incentive compensation. Occasionally, designs incorporate an initial period, perhaps the first four weeks, where benefits are provided at 100% of pre-disability income before transitioning to a decreased percentage, such as 70%, thereafter.

Long-term plans generally settle within the 50% to 70% range, with 60% and 66⅔% being commonly adopted percentages. Plans aligning disability benefits with a percentage of earnings often impose a maximum dollar limit on the benefits.

Short-term disability plans usually entail a waiting period, during which the covered employee must be disabled for benefits to commence. While accidents often bypass this waiting period, disabilities arising from illnesses may require a period ranging from one to seven days. If sick leave is available, this waiting period may be extended.

Studies have demonstrated that waiting periods effectively lower the costs of disability programs. For instance, not having a waiting period resulted in nearly 20% of all employees using disability benefits annually, whereas a 14-day waiting period reduced this figure to less than 10%. A 29-day waiting period further reduced it to less than 5%. Employers can strategically manage costs by implementing longer waiting periods within their disability programs.

Navigating Disability Benefits: Striking a Balance

Despite compelling statistics, employers are tasked with finding a delicate compromise between extended waiting periods and potential hardships for employees.

Short-term disability benefits, typically outlined in insurance policy contracts, usually extend up to a maximum of 26 weeks. Long-term benefits seamlessly follow short-term benefits and may persist for up to two years or even the lifetime of the disabled employee, contingent on the cause of the disability—whether by accident or illness.

Coordination of benefits provisions is a common feature in most disability plans, preventing benefits from surpassing the employee's pre-disability gross income. In adherence to this principle, disability income from an insured plan may be adjusted if alternative income sources are identified from other disability programs. Employer-sponsored programs strategically complement disability benefits available through various channels, including workers' compensation, Social Security, pension plans, sick-leave plans, and other sources.

Ensuring holistic support during disability, many companies sustain other benefits such as pension, life insurance, and medical insurance. The significance of life and medical coverage is underscored by the recognition that individuals in a disabled state may struggle to secure adequate coverage independently due to their health condition.

In response to evolving needs, numerous companies introduce supplemental long-term disability programs. These plans encompass employer-paid basic coverage while allowing employees to augment their coverage by contributing premiums. Termed as buy-up plans, they serve as a cost-containment measure by shifting a portion of the insurance cost to employees

A pivotal component in long-term disability programs is the rehabilitation provision, designed to encourage employees to gradually resume regular employment and reduce dependence on disability income. During this rehabilitative phase, employees receive a reduced amount of benefits. If it becomes evident that the employee is unfit for regular employment, full long-term benefits are reinstated.

Employers, recognizing the paramount importance of reintegrating disabled workers into gainful employment, often embrace integrated disability management. This approach involves a single provider overseeing rehabilitation across all disability programs, streamlining the process and fostering a comprehensive strategy to support employees on their journey to recovery and professional reengagement.

Long-Term Care Benefits: Addressing the Growing Need

The provision of long-term benefits to employees is becoming increasingly prevalent, spurred by a recognized long-term care crisis in the United States, as emphasized by the U.S. Department of Labor's Advisory Council on Employee Welfare and Pension Benefit Plans. The underlying cause is the aging American population, with the U.S. Census Bureau projecting a doubling of citizens aged 65 or older to 70 million by 2030, and a near doubling of those aged 85 and older to about 8.5 million during the same period. This demographic shift signals a heightened demand for long-term care services.

The average stay in a nursing home, approximately 2.5 years on average, is not exclusive to the elderly; younger individuals also require extended care due to various factors such as birth defects, mental illness, accidents, and more. The associated costs can range from $60,000 to $110,000 or more per year.

In response to this national concern, employers are increasingly integrating long-term care insurance into their employee benefits portfolios. The Health Insurance Association of America (HIAA) reports that over 1 million policies have been sold through 3,500 employers, with recent surveys indicating that nearly 1.5 million individuals receive long-term care protection through their employers, constituting approximately 25% of all long-term care insurance. Employees are actively seeking out this insurance during their working years when premiums are more affordable.

Long-term care insurance is tailored to provide coverage for at least one full year to employees in need of non-acute care, typically in the form of personal care services. This coverage is commonly offered through either an insurance product or voluntary plans, reflecting a strategic response to the escalating demand for extended care services in the face of demographic shifts and evolving healthcare needs.

Long-Term Care Plans: Navigating Eligibility and Coverage

Insurance companies that underwrite group life and health insurance policies often extend their offerings to include long-term care plans for groups. Conversely, those specializing in individual insurance commonly provide voluntary plans.

To qualify for ownership of a long-term care policy, an individual must meet one of the following two eligibility definitions:

Chronic Illness: Demonstrating the need for extended care due to a chronic illness or disability.

Substantial Cognitive Impairment: Suffering from severe cognitive impairment, often associated with conditions like dementia or Alzheimer's disease, necessitating supervision for the patient's health and safety.

Long-term care, as defined, extends beyond basic medical treatment or nursing care to assist individuals unable to perform Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) without substantial assistance for at least 90 days due to a loss of functional capacity. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) identifies six ADLs, including bathing, dressing, moving, toileting, eating, and continence.

Services covered by long-term care insurance can be administered in nursing homes, the patient's home, or through community services such as visiting nurses, home health aides, home-delivered meals, and adult daycare centers. Long-term care insurance serves as a crucial financial safeguard against the substantial costs associated with extended care, addressing a significant risk that employees must protect themselves against. Consequently, long-term care planning has emerged as a crucial workplace concern, with employer-sponsored long-term care benefits gaining considerable popularity.

Group long-term care plans are typically funded through employee contributions, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) has provided employers with tax incentives for offering such plans. Insurance companies offer a range of benefit options and design flexibility to employers, ensuring premiums remain at a reasonable cost. This approach seeks to strike a balance between addressing the critical need for long-term care coverage and providing an economically viable solution for both employers and employees.

Comprehensive Coverage in Long-Term Care Insurance Plans

Long-term care insurance plans encompass a broad spectrum of care services, ensuring coverage for various needs:

Nursing Home Care: This category includes:

Skilled Care: Nursing or rehabilitative care supervised by medical personnel, following a physician's order.

Intermediate Care: Occasional nursing and rehabilitative care initiated by a physician's order.

Custodial Care: Assistance with daily personal needs, as determined by the patient.

Assisted Living Facility Care: Provided in facilities designed for elderly individuals who can no longer manage their daily needs but do not yet require nursing home-level care.

Home Health Care: Services administered in the patient's home, catering to various medical and non-medical needs.

Hospice Care: Covered under long-term care plans, hospice care focuses on alleviating physical and psychological pain associated with end-of-life situations. Counseling services for the patient's relatives are also included, and care can be provided in a facility or at home.

Alzheimer’s Facility Care: Many states mandate coverage for Alzheimer's facilities under long-term care plans. The level of care for Alzheimer's disease and other degenerative conditions is stipulated under the same terms as any other chronic illness. Consequently, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, or at-home services may be classified as Alzheimer's facilities, depending on the insurance policy's language.

In summary, long-term care insurance offers comprehensive coverage, ensuring that individuals have financial support for a range of care services, from skilled nursing to assistance with daily activities, in various settings such as nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and even in the comfort of one's home.

Comprehensive Home Healthcare Services under Long-Term Care Plans

Home healthcare services, integral components of long-term care insurance plans, encompass a wide range of provisions tailored to support individuals in their residences. These services include:

Purchase or Rental of Medical Equipment:

This covers essential medical devices, including emergency alert systems, enhancing the safety and well-being of the patient at home.

Home Modifications:

Ensures accessibility by covering modifications such as wheelchair ramps or adjustments made for restroom accessibility, facilitating a more accommodating living environment.

Adult Daycare Services:

Provides daytime care services at a center for patients living at home, particularly when family members are unavailable during the day.

Caregiver Training:

Offers training to family members to ensure they can provide appropriate care for the patient at home, enhancing the overall quality of care.

Homemaker Companion Services:

Involves assistance with household tasks like cooking, shopping, cleaning, and bill paying by a homemaker companion employed by a state-licensed home healthcare agency.

Prescription Drugs and Lab Services:

Covers essential medications and laboratory services, typically offered in hospitals or nursing homes.

Additional Benefits:

Encompasses various other benefits such as care coordination services, chore services, bed reservation reimbursement, coverage for medical equipment, home-delivered meals, spousal discounts, and survivor benefits.

Eligibility for these benefits is typically determined based on criteria such as deficiencies in performing Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and cognitive impairment. Long-term care plans offer guaranteed renewability, a 30-day "free look" period, coverage for Alzheimer’s disease, provisions for waiving premiums, and unlimited/lifetime nursing home periods. Additionally, these plans incorporate features like inflation protection and nonforfeiture benefits, emphasizing a holistic approach to long-term care coverage.

Improved Cost Explanation:

Long-Term Care Insurance:

Employees are responsible for covering the costs of long-term care insurance, with premiums structured in five-year increments. The premium rates are age-dependent, with individuals aged 40 to 44 paying approximately one-third to half of what those aged 60 to 64 would pay. Once a coverage is chosen, premiums remain fixed until the employee enters a new age bracket. Premiums are typically payable for life. The insurance policies operate in one of two ways:

Reimbursement Basis: This model reimburses the insured for actual expenses, up to a specified daily limit (e.g., up to $200 per day), with coordination required with Medicare, except when Medicare acts as the secondary payer.

Per-Diem Basis: Benefits are paid irrespective of actual costs, with the daily limit honored even if actual expenses are lower.

Group Business Travel Insurance Benefit:

Business travel accident insurance offers Accidental Death and Dismemberment (AD&D) benefits to employees involved in accidents during business-related travel. For instance, a group of employees flying for a business conference is covered under this policy.

AD&D benefits are extended to groups of ten or more employees traveling for business, typically fully funded by the employer. Companies commonly provide Business Travel Accident (BTA) insurance at no cost to eligible employees, who are automatically covered without enrollment. Benefit structures may be influenced by job classification, annual earnings, a salary multiple, or a standardized flat amount.

A typical benefit schedule may equate to five times the annual base salary, with a maximum amount up to twice this figure, not exceeding $5 million, contingent on the group's size and benefits. BTA insurance disburses a percentage of coverage based on the nature of the loss. Coverage options may encompass 24-hour protection for business purposes only or both business and pleasure. Optional services can be incorporated into this plan.

Enhanced BTA Insurance Benefit Program Details:

The specifics of a standard Business Travel Accident (BTA) insurance benefit program are outlined as follows, providing comprehensive coverage and financial protection for employees. The benefit amount is set at ten times the employee's annual salary, capped at a maximum of $150,000, with an aggregate limit of $3 million. The plan encompasses a range of standard benefits, including:

• Loss of life

• Loss of speech

• Loss of hearing

• Loss of hand, foot, or eye

• Loss of thumb and index finger on either hand

• Paralysis benefits

Additionally, the policy offers the following payout structure:

• 100% of the coverage amount for the accidental loss of life; loss of two limbs; complete loss of eyesight (both eyes); loss of one limb and the sight of one eye; loss of speech and hearing; or complete loss of movement in both upper and lower limbs (quadriplegia).

• 75% of the coverage amount for the accidental loss of movement in both lower limbs (paraplegia).

• 50% of the coverage amount for the accidental loss of one limb; loss of sight in one eye; loss of speech or hearing; or loss of movement in both upper and lower limbs on one side of the body (hemiplegia).

• 25% of the coverage amount for the accidental loss of the thumb and index finger of the same hand.

The full coverage amount is disbursed under the following conditions, ensuring comprehensive protection for employees: [Include specific conditions and circumstances under which the full coverage amount is paid, such as detailed in the policy terms and conditions].

Enhanced Benefit Provisions in BTA Insurance:

This BTA insurance plan goes beyond the ordinary to provide comprehensive coverage, acknowledging various circumstances that may arise. The detailed provisions are as follows:

Extraordinary Commutation:

Benefits are extended if an employee is injured in a covered accident while commuting between home and work, using unconventional transportation during exceptional circumstances like transportation strikes, power failures, major civic breakdowns, and the like.

Personal Deviation (Sojourn):

Benefits cover injuries resulting from accidents worldwide during personal business or travel while on a covered business trip.

Paralysis Benefit:

Compensation is provided for injuries leading to complete and irreversible loss of movement in one or more limbs, including paraplegia and quadriplegia.

Permanent Total Disability:

Benefits are paid if the employee or their spouse becomes permanently disabled within 365 days of the accident.

Accidental Total Disability:

Weekly benefits are disbursed in the event of total disability resulting from a covered accident.

Additional Provisions:

Criminal Acts Coverage:

Benefits are granted if the employee is injured due to a violent crime such as kidnapping, robbery, or hold-up.

Specified Aircraft:

Compensation is provided if an employee is injured while a passenger on an aircraft owned, leased, or operated by the policyholder.

Spouse/Child (Children) on a Business Trip:

Additional benefits are paid if a spouse/child accompanies the employee on a business trip. Spouse coverage is set at $50,000, and each child at $25,000.

Relocation of Spouse/Child (Children):

Coverage is extended for injuries during a relocation trip, with a spouse covered at $50,000 and each child at $25,000.

Rehabilitation Benefit:

If benefits are payable for an injury other than loss of life, expenses for rehabilitative training are covered.

Spouse Education Benefit:

In the event of the death of the employee or their spouse, expenses for occupational training for the surviving spouse are covered.

Child Education Benefit:

Upon the death of the employee or their spouse, this provision covers expenses for each dependent child qualifying as a student.

Coma Benefit:

A portion of benefits is paid if the employee or a family member becomes comatose within a specified time after an injury and remains in a coma for a defined period.

Seatbelt Benefit:

Additional benefits are provided for death caused by injuries sustained in a motor vehicle while wearing a seatbelt.

Daycare Benefit:

In case of the death of the employee or their spouse, the provision covers each dependent child under a certain age enrolled or to be enrolled in a daycare program.

Therapeutic Counseling Benefit:

Occasionally, benefits cover necessary therapeutic counseling expenses.

Enhanced Explanation of Tax Implications for Group Life Insurance:

The tax implications associated with the earlier described risk benefit plans are intricately woven into federal income tax, estate tax, federal gift taxation, and state taxes. The substantial growth of these plans can be attributed to the favorable federal tax treatment they receive. Notably, the tax considerations are different for employer contributions and employee contributions to group life insurance policies.

Employer Contributions:

All contributions made by employers to group life insurance policies are fully tax-deductible under Code Section 162. This deduction is grounded in the recognition that providing such coverage is an ordinary and necessary business expense for the employer. However, adherence to Code Section 264 is essential, as it precludes any deduction if the employer is named as the beneficiary of the plan.

Employee Contributions:

Contrastingly, contributions made by employees are not tax-deductible, given that they are viewed as personal expenses for life insurance. Payroll deductions, as authorized by employees for the policy, are incorporated into the employee's gross income and duly reported in W-2s by employers.

Code Section 79 and Group Term Life Insurance:

A notable exception to the general tax treatment is found in Code Section 79, which offers favorable tax treatment for employer contributions categorized as group term life insurance. To qualify for this treatment, the policy must meet specific criteria:

Excludable Death Benefits: Death benefits must be eligible for exclusion from federal income taxes.

Inclusive Employee Coverage: The plan should extend coverage to all employees, with any deviations based on factors such as age, marital status, and other employment-related considerations.

Employer-Carried Policy: The employer must carry the policy, even if costs are shared with employees.

Master Contract or Group of Individual Policies: The policy must be covered by a master contract or a group of individual policies. This includes scenarios where the employee is not the policyholder, but the employer extends coverage from the master contract to employees, either through negotiated trusteeships or as part of multi-employer welfare arrangements.

Enhanced Explanation of Group Term Life Insurance Tax Implications:

Plan Structure and Supplemental Coverage:

The group term life insurance plan should disallow individual coverage selection. However, flexibility can be introduced through supplemental plans. These supplemental plans empower employees to tailor coverage amounts to their preferences, offering alternative benefit schedules based on their contribution levels.

Employee Count and Participation Criteria:

Coverage must be extended to a minimum of ten full-time employees, including those yet to fulfill the stipulated waiting period. Even non-participating employees, who have opted not to join the plan, are considered participants, provided they aren't obligated to contribute to benefits outside the group term life insurance policy.

Exceptions and Tax Code Guidance:

Certain scenarios exempt Section 79's application. For instance, when group term life insurance is issued to trustees of a qualified pension plan for death benefits, the full amount paid by the employer becomes taxable income for the employee. In such cases, alternative sections of the tax code guide the administration of the plan.

Non-Taxable Employer Contributions:

Employer contributions do not result in taxable compensation in three specific situations:

Disability Loss of Coverage: When an employee loses coverage due to disability.

Charitable Beneficiary: When a qualified charity is designated as the plan beneficiary.

Employer as Beneficiary: If the employer has been named as a plan beneficiary for an entire year.

Retired Employee Coverage:

Retired employee coverage falls under Section 79, treated similarly to active employees. Amounts exceeding $50,000 are considered taxable income for retirees. The initial $50,000 is non-taxable, except for the excess amount minus any employee contributions for comprehensive coverage, which becomes taxable.

Exclusion and Calculation Under Section 79:

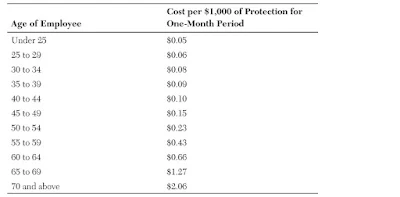

Up to $50,000 of employer-provided group term life insurance is excluded from the employee's income, given compliance with Section 79 requirements. This section mandates that group life insurance policies adhere to a formula preventing individual selection. Taxable income, following this outline, is determined using the Uniform Premium Table.

Optimized Explanation of Group Term Life Insurance Taxation:

To exempt the initial $50,000 of group term life insurance policies from taxation, employers should structure coverage as a fixed amount or as a multiple of an employee's earnings. Referring to Table 4.3, any coverage surpassing $50,000 becomes taxable, and these excess costs should be detailed on the employee's W-2 form. Additionally, any value exceeding $2,000 for dependent group term life insurance, covering the spouse or dependents of the employee, must also be reported on the W-2.

Calculation of taxable compensation in this policy involves taking the cost from the table corresponding to the employee's age group, determined by their age at the year's end. This cost is then multiplied by an appropriate thousand-dollar increment above the $50,000 threshold. Monthly costs are subsequently converted into an annual figure for accurate reporting.

All group term life insurance plans undergo nondiscrimination tests, as detailed later in this chapter. Failure to pass these tests renders the $50,000 exclusion unavailable to key employees (as defined in the next section) under the plan. In such cases, the full coverage value minus employee contributions becomes taxable income. The benchmark for taxation is the higher of the actual costs or the costs outlined in Table 4.3, as discussed earlier. This ensures equitable treatment and compliance with nondiscrimination standards.

Improved Explanation of Nondiscrimination Rules:

Nondiscrimination Rules for Qualified Group Term Insurance Plans:

Any group term insurance plan that qualifies under Section 79 is subject to stringent nondiscrimination rules. Failing these essential tests renders the plan inaccessible to key employees, as previously defined. For key employees, the value of full coverage, excluding their contributions, becomes taxable income, determined by the higher of actual costs or Table 4.3 costs.

Definition of Key Employees:

A key employee falls into one of the following categories:

An officer earning over $160,000 annually (Officers defined as the greater of three employees or 10% of all employees in the company.)

A 5% owner of the company, holding 5% or more of its outstanding stock.

An employee owning 1% of the company's outstanding stock, earning over $160,000 annually.

Eligibility Requirements and Non-Discrimination Criteria:

Eligibility requirements are not considered discriminatory under the following conditions:

At least 70% of all employees are eligible to participate in the plan.

At least 85% of all employees are not categorized as key employees.

The IRS determines that employees belong to a nondiscriminatory classification.

Employees with less than three years of service, part-time, and seasonal employees may be excluded from the first 70% eligibility test. The plan achieves nondiscrimination status if benefits, either in type or amount, do not disproportionately favor key employees. Benefits can be based on a uniform percentage of an employee's salary.

Tax Treatment of Life Insurance Proceeds:

Under Code Section 101, life insurance proceeds are not taxable income if distributed as a lump sum upon the death of the employee. If distributed in installments, only the interest earned is considered taxable income for the beneficiary.

Estate Tax Considerations (Code Section 2042):

Proceeds from an employee's contract, even if paid to a beneficiary, become part of the employee's estate for federal tax purposes if the coverage was owned at the time of death. However, no estate taxes apply to amounts paid to the surviving spouse. To mitigate estate taxes, life insurance proceeds are often assigned to another person, typically the named beneficiary, provided it aligns with contract terms and relevant state laws.

The tax implications of supplementary life insurance policies hinge on whether the policy is a distinct contract or an integral part of the basic policy. When structured as a separate policy and meeting the criteria for a Section 79 group life insurance program, the coverage amount from a supplementary policy is aggregated with all other coverage for calculation purposes under Table 4.3. Employee-paid premiums for this supplemental coverage are added to deductions, influencing the calculation of final taxable income. It's noteworthy that not all supplemental plans qualify under these provisions; eligibility is contingent on employee rates aligning with or exceeding Table 4.3.

AD&D (Accidental Death and Dismemberment) plans have a distinct tax treatment. The premiums paid for AD&D plans are classified as health insurance premiums rather than group life insurance premiums. Nevertheless, these costs remain deductible for employers as ordinary and customary business expenses. Dependent life insurance premiums covered by the employer are fully deductible, with employer contributions not incurring tax for employees, provided the benefits remain modest. Notably, death benefits under such programs are exempt from taxation, providing an additional layer of financial security for beneficiaries.

Enhanced Explanation of Tax Implications for Group Disability Programs:

Deductibility of Employer Contributions:

Similar to group life insurance, employer contributions to group disability insurance programs are fully deductible as normal and customary business expenses under Code Section 162, provided the employee's compensation is reasonable.

Tax Implications for Employees (Section 106):

Contributions made for disability insurance under Section 106 usually do not have tax implications for employees. However, the taxation of benefits under a disability or sick-leave plan depends on whether the plan is fully contributory, partially contributory, or noncontributory. Most disability insurance programs fall into the noncontributory category, where the employer bears the full cost, and the benefits are included in the employee's gross income.

Tax Credits for Permanent Disability (IRS Criteria):

For employees who are permanently or totally disabled, the IRS provides tax credits. The IRS utilizes the Social Security Administration's definition of disability, considering activities related to consistent employment but excluding ordinary personal and household maintenance. The ability to manage household activities does not negate a claim for permanent and total disability, though it is a factor considered in the evaluation.

Claiming the credit involves obtaining a physician's statement certifying the disability. Notably, disability income does not include payments from plans not specifically designed for such benefits, such as 401(k) accounts or cash payments for accrued personal or vacation days.

Taxation of Benefits in Partially Contributory Plans:

In partially contributory plans, benefits are taxable based on the proportion of employer premiums compared to total premiums. Social Security taxes apply to all taxable disability benefits for the last month worked by an employee plus the subsequent six months.

Tax Credits for Partially Contributory Plans:

Tax credits for such plans vary:

Maximum Credit:

$750 for a single person

$1,125 for married couples filing jointly

$562.50 for married individuals filing separately

Credit Limitation:

The credit is capped at the received disability benefits.

It is reduced by 7.5% for adjusted gross income, including disability income, exceeding:

$7,500 for single individuals

$10,000 for married couples filing jointly

$5,000 for married individuals filing separately

The credit is further reduced by 15% for tax-free income received as pension, annuity, or disability benefits from governmental programs like Social Security. This reduction is particularly relevant as disability payments are often coordinated with Social Security, impacting the tax credit available to individuals receiving these payments.

Enhanced Explanation of Tax Implications for Disability Insurance Programs:

Employer Contributions and Tax Treatment:

Employers commonly exclude their contributions to disability insurance programs as they are recognized as ordinary and necessary business expenses. However, since benefits paid to employees are treated akin to wages, a withholding tax concern arises. Payments to disabled employees or their beneficiaries are considered taxable wages for six months following the last date of service under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) and the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) withholding rules.

Tax Responsibility and Withholding:

A critical taxation consideration revolves around determining the entity responsible for withholding FICA and FUTA taxes and remitting payments to the federal government. Typically, employers bear this responsibility. However, in certain scenarios, third-party payers or agents may assume this role based on their liability for losses. The differentiation between third-party payers and agents hinges on who assumes the risk of losses. Independent insurance companies fall under the category of third-party payers and are regarded as employers for taxation purposes since they are accountable for making payments to disabled employees and their dependents. Consequently, these companies are obligated to withhold and remit both FICA and FUTA taxes.

Other Agents and Taxation Responsibility:

Various entities, such as payroll services, accounting firms, or an employer's internal payroll department, may administer disability programs on behalf of an employer. From a technical standpoint, these entities do not assume a risk of loss because their role is strictly administrative. As a result, the employer remains responsible for FICA and FUTA taxes.

Exceptional Cases and Agreements:

An exception exists when an agreement between the employer and an external agency explicitly defines the party responsible for FICA taxes. In such cases, the terms of the agreement dictate the taxation responsibility, offering flexibility in the allocation of tax-related duties between parties involved in administering disability programs.

Enhanced Explanation of Tax Implications for Long-Term Care Insurance:

Employer Deductions and Employee Benefits:

The federal tax code extends favorable treatment to long-term care insurance, allowing employers to deduct both the setup costs of a long-term care plan for their employees and contributions made toward tax-qualified premiums. If an employer covers all or a portion of tax-qualified premiums for an employee, the entire contribution is deductible as a business expense, without age limitations. The contribution made by the employer is entirely excluded from the employee's adjusted gross income (AGI).

Employee Tax Benefits:

Long-term care insurance provides tax benefits to employees as well. Premiums for these benefits are classified as medical expenses and are deductible to the extent that, combined with other unreimbursed medical expenses, they surpass 7.5% of the worker's AGI. If the employer covers only a part of the premium, employees can apply the remainder they pay toward their medical expenses, up to the eligible premium amount, qualifying for a similar deduction.

State-Specific Tax Incentives:

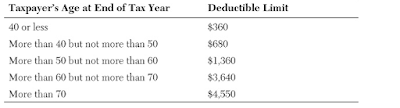

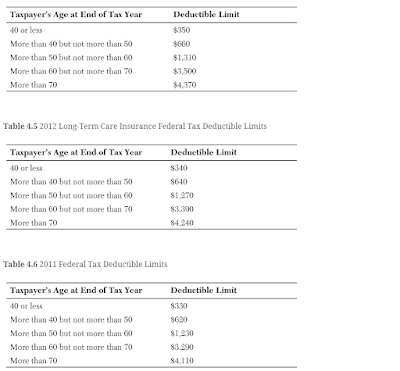

Certain states offer tax incentives to encourage the purchase of LTC insurance. However, taxpayers may need to meet state-specific requirements to qualify for deductions or credits related to this insurance. Tax-qualified LTC premiums are considered a medical expense for itemization purposes, deductible to the extent that they exceed the amount needed to meet the employee's AGI. The deductible portion is limited to eligible LTC insurance premiums, as defined by Internal Revenue Code 213(d), based on the age of the employee.

Individual Taxpayer Benefits:

For individual taxpayers, premiums for tax-qualified long-term care insurance covering themselves, their spouse, or any dependents (such as parents or children) can be treated as a personal medical expense. This provision provides individuals with the flexibility to leverage tax benefits associated with long-term care insurance, supporting the financial aspects of caring for themselves and their family members.

The annual maximum deductible amount for each employee is contingent on their attained age at the conclusion of the current taxable year, as detailed in Tables 4.4, 4.5, 4.6, and 4.7. These maximums are subject to indexing and experience annual increases to accommodate adjustments for inflation.

Employer-paid long-term care benefits remain non-taxable, providing a financial advantage; out-of-pocket expenses incurred for long-term care are deductible; and benefits from a tax-qualified long-term care insurance policy, as defined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), are generally exempt from income taxation, with a notable exception: under per-diem contracts, proceeds are excludable up to a daily limit of $300.

HIPAA establishes a framework for favorable tax treatment of qualified long-term care insurance programs, but the insurance contract must meet specific criteria:

The insurance contract should exclusively provide coverage for long-term care services.

Services reimbursable under Medicare are not covered by the contract.

Guaranteed renewability for the contract is a prerequisite.

The contract must lack cash surrender value or any other form of funding that could be borrowed, paid, assigned, or pledged as collateral.

Premium refunds and plan dividends must contribute to reducing premiums or increasing future benefits.

The policy, as part of the contract, must comply with relevant consumer protection legislation, ensuring fair and ethical practices in providing long-term care coverage.

This chapter delves into various other risk benefits plans, covering aspects such as group term life insurance benefits, group dependent life insurance benefits, supplemental life insurance benefits for both employees and dependents, disability benefits, group accidental death and dismemberment plans, long-term care plans, and group travel accident insurance. It explores the accounting, tax, legal, actuarial, and financial dimensions associated with these plans.

Group term life insurance consolidates life coverage for a group of individuals, and tax implications for this type of insurance involve federal income taxes, estate taxes, federal gift taxes, and state taxes. The chapter underscores the growth of these plans due to their overall favorable federal tax treatment.

Similar to group term life insurance, employer contributions to group disability insurance programs are fully deductible as normal and customary business expenses under Code Section 162, contingent on the reasonableness of employee compensation.

The tax implications of supplementary life insurance policies hinge on whether they are written separately or as part of a basic term life insurance policy. Additionally, premiums for accidental death and dismemberment (AD&D) plans are treated as health insurance premiums, deductible by employers as part of regular business expenses.

In the realm of long-term care plans, the federal tax code allows employers to deduct both the setup costs and contributions made toward tax-qualified long-term care insurance premiums as business expenses.

Key Concepts in This Chapter:

Group term life insurance benefits

Group dependent life insurance benefits

Supplemental life insurance benefits for employees and their dependents

Disability benefits

Group accidental death and dismemberment plans

Long-term care plans

Group travel accident insurance

Nondiscrimination rules

Chapter 5: Retirement Plans

Aims and Objectives:

Introduction to Pension Plans: Provide a brief overview of pension plans and their significance in retirement planning.

Types of Pension Plans: Explore the distinctions between defined contribution plans and defined benefit pension plans.

Impact of ERISA: Discuss the influence of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) on pension plans.

Accounting Issues: Examine accounting considerations for both defined contribution plans and defined benefit pension plans.

Pension Benefit Obligations: Clarify the concept of pension benefit obligations.

Pension Plan Assets and Expenses: Explore the management of pension plan assets and associated expenses.

Financial Reporting: Discuss the financial reporting standards and practices for pension plans.

Accounting Recordkeeping: Address the essential accounting recordkeeping requirements for pension plans.

Pension plans play a pivotal role in the economy as the primary tool individuals use to save for retirement, either through employer-sponsored arrangements or personal initiatives. These plans, with substantial financial assets, serve as major sources of investment and equity capital, contributing to the sustainability and growth of the overall economy.

Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA):

The chapter delves into the impact of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), a regulatory framework shaping the landscape of pension plans and safeguarding the interests of plan participants.

Types of Pension Plans:

Distinguish between defined contribution plans and defined benefit pension plans, elucidating their unique characteristics, advantages, and considerations.

Accounting and Financial Aspects:

Explore the accounting intricacies related to pension plans, encompassing pension benefit obligations, assets, expenses, and financial reporting standards. The chapter also delves into the meticulous accounting recordkeeping required for effective pension plan management.

By providing a comprehensive understanding of these crucial aspects, the chapter equips readers with the knowledge needed to navigate the complex terrain of retirement planning and pension management.

Chapter 5: Retirement Plans

Overview:

In this chapter, we explore the critical landscape of retirement plans, shedding light on their conceptual framework, types, regulatory influences, and the intricate financial and fiduciary responsibilities associated with managing substantial pension assets.

Pension Assets Landscape:

As of 2010, pension assets in the United States reached an astounding $6.2 trillion, with defined benefit plans comprising $2.4 trillion and defined contribution plans amounting to $3.8 trillion. These colossal figures underscore the significant role played by corporate pension investment managers, trustees, and retirement plan committees, predominantly composed of organizational leaders. Endowed with fiduciary responsibility, they navigate the complex task of investing these assets to optimize returns, ensuring financial security for employee retirement and fostering talent retention.

Multifaceted Challenges:

Managing pension plans involves grappling with multifaceted challenges encompassing financing, taxes, accounting, legal compliance, and auditing. The chapter explores these issues from diverse perspectives, considering political, societal, union relations, financial sustainability, and personal financial security.

Retirement Crisis Concerns:

An essential introduction delves into the pervasive concerns surrounding the retirement crisis, not only in the United States but also in several other countries. The narrative acknowledges the extensive coverage and discussions in the press regarding this pressing issue.

Insights from a Senate Report:

Highlighting the severity of the situation, a 2012 report from the U.S. Senate Committee on Health Education Labor and Pensions, titled “The Retirement Crisis and a Plan to Solve It,” is referenced. This report provides a comprehensive description of the pension crisis facing the United States, setting the stage for a detailed exploration of solutions and strategies.

This chapter aims to equip readers with a nuanced understanding of the intricacies surrounding retirement plans, enabling them to navigate the evolving landscape of pension management and contribute to addressing the challenges posed by the ongoing retirement crisis.

Chapter 5: Retirement Plans - Addressing the Crisis

The Retirement Income Deficit:

A staggering retirement income deficit of $6 trillion looms, reflecting the alarming gap between what individuals have saved for retirement and the actual amount required. A significant portion of Americans, half to be precise, have accumulated less than $10,000 in retirement savings, setting the stage for a dire situation as aging citizens exit the workforce.

Challenges of Extended Life Expectancy:

Compounded by the rising life expectancy, a byproduct of improved living conditions and advancements in healthcare, the crisis deepens. This places an immense strain on families, communities, and the societal safety net, as retirees grapple with financial inadequacy in their later years.

Breakdown of the Three-Legged Stool:

Many attribute the retirement crisis to the breakdown of the "three-legged stool" approach: personal savings, employer retirement benefit programs, and government-provided Social Security. Dwindling personal savings, the shift from defined benefit to defined contribution plans, and instability in the federal social security structure collectively weaken this foundation. Employees, uncertain about the reliability of employer-sponsored plans, increasingly contribute personally to ensure their financial security.

Importance of Retirement Plans for Employers:

For employers, pension/retirement plans represent a crucial strategic element within the broader benefits portfolio. Employees, in turn, prioritize retirement benefits as the second-most important aspect, following healthcare.

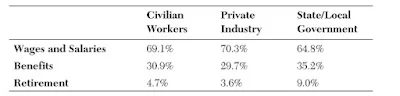

Bureau of Labor Statistics Insights:

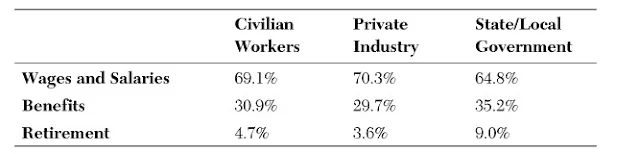

The Bureau of Labor Statistics' March 2013 release provides a comprehensive view of retirement plans in the United States, offering valuable insights into the prevalence and significance of these plans.

Implications and Solutions:

This chapter aims to delve into the multifaceted implications of retirement planning, encompassing design, development, and technical aspects such as accounting, finance, legal considerations, and tax-related issues. By understanding these intricacies, employers and employees can collaboratively navigate the evolving landscape of retirement benefits, paving the way for informed decisions and strategic solutions to address the crisis at hand.

Retirement Benefits Landscape:

Disparity in Access:

The landscape of retirement benefits mirrors the trends observed in medical care benefits. In the private sector, a notable 74 percent of full-time workers enjoy access to retirement plans, a stark contrast to the 37 percent of part-time workers who have similar benefits. This discrepancy underscores the challenges faced by part-time employees in securing comprehensive retirement provisions.

Establishment Size Matters:

Access to retirement benefits varies significantly based on the size of the establishment. While 49 percent of workers in small establishments have access to retirement plans, a more substantial 82 percent of workers in medium and large establishments enjoy similar benefits. This suggests that the scale and resources of the employer play a pivotal role in determining the availability of retirement benefits for their workforce.

Defining Access:

It's important to note that a worker is considered to have access to a medical or retirement plan if their employer provides such plans, irrespective of the worker's decision to enroll or actively participate in these plans. The focus is on the availability of employer-provided plans rather than the employees' individual choices to engage with them.

Cost Considerations for Employers:

The relative importance of retirement savings, gauged from the employer's cost perspective, is outlined in Table 5.1. This sheds light on the varying degrees of emphasis placed on retirement benefits by employers, potentially influencing the overall compensation structure within organizations.

Retirement Benefit Landscape: A Shift in Trends

Survey Insights:

A comprehensive survey on employee benefits conducted by the Society of Human Resource Management in 2012 provides valuable insights into the prevailing trends in retirement plans. Of the companies surveyed, a substantial 92% indicated that they offer a defined contribution retirement savings plan. This signifies a predominant shift towards defined contribution plans in the contemporary employment landscape.

Defined Benefit Pension Plans: A Decline:

In contrast, the survey revealed a notable decline in the prevalence of defined benefit pension plans. Only 21% of the surveyed companies reported offering such plans. This decline underscores a broader shift away from traditional pension structures towards more contemporary retirement savings models.

Frozen Defined Benefit Plans: A Restricted Landscape:

Another noteworthy finding from the survey is that 12% of the organizations reported that their defined benefit pension plans were frozen. This indicates that these plans were no longer available to new employees, further substantiating the diminishing popularity of traditional pension plans. The freezing of these plans suggests a strategic reassessment by organizations in light of evolving employee benefit preferences and economic considerations.

These survey findings collectively reflect a dynamic shift in the retirement benefits landscape, with a clear preference for defined contribution plans and a decreasing reliance on traditional defined benefit pension structures.

This survey delved into another facet of defined benefit plans by examining their historical prevalence trends. Between 2008 and 2012, there was a noteworthy shift in the landscape, with defined contribution benefits plans experiencing a rise from 84% to 92%, while the prevalence of defined benefit pension plans declined from 33% to 21%. This chapter undertakes an exploration of the underlying reasons behind these trends, with a primary focus on the financial and accounting perspectives.

The insights provided in this chapter draw from the 11th annual retirement survey conducted by the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies. This survey specifically delves into the perspectives of employees regarding retirement programs. Notable findings from this study are pertinent to our analysis of the technical dimensions of retirement programs, adding depth to our understanding.

The survey uncovered the following key insights:

Employers across the board, especially in small companies, increasingly recognize the significance of retirement packages for their employees.

There is a prevailing sense of confidence among employers regarding the retirement plan options they provide.

Employees in larger companies appear to be in a more favorable position for retirement compared to their counterparts in smaller companies.

Large companies are more inclined to offer defined benefit pension plans, contributing to the retirement landscape dynamics.

The majority of employers consistently assert that robust retirement benefits hold greater appeal to potential candidates than a higher salary.

Notably, a growing number of employers, particularly in small companies, now acknowledge the importance of retirement plans to their employees, reflecting an upward trend in this awareness.

Pension plans come in two main types, each offering distinct structures and benefits:

Defined Contribution Plans:

These plans commit to a fixed annual contribution to a pension fund, often a percentage of the employee's salary (e.g., 6%).

Employees have the flexibility to choose from a range of investment options, typically involving stocks or fixed-income securities.

Retirement benefits hinge on the fund's size at the time of retirement.

Unlike defined benefit plans, there's no assurance of a specific retirement benefit amount.

Both the employee and employer contribute to an individual account, with the employee managing investment decisions.

Employers may match a percentage of the employee's contributions.

Popular examples include the Traditional 401(k), Safe Harbor 401(k), Simple 401(k), and Automatic Enrollment 401(k).

Other variations encompass the Simple IRA plan, Simplified Employee Pension Plan (SEP), Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP), and Profit-Sharing Plan.

Defined Benefit Plans:

These plans commit to fixed retirement benefits based on a predetermined formula.

The formula typically factors in the employee's years of service, annual compensation (often based on the final year or an average for the last few years), and age.

Employers bear the responsibility of ensuring adequate funds to fulfill the promised benefits.

Defined benefit plans are funded by the employer and guarantee a specific monthly payout upon retirement.

The payout may be a fixed amount per month (e.g., $1,000) or calculated using a formula based on factors like average income for the employee's last five years multiplied by total years of service (e.g., 1% of the average income for each year of service).

In summary, defined contribution plans offer flexibility and are dependent on contributions and investment performance, while defined benefit plans provide a predetermined, employer-funded retirement benefit based on a specified formula.

Employers bear the responsibility of ensuring ample financial resources to fulfill agreed-upon benefits for their employees. One prevalent mechanism for this is the defined benefit plan, where the employer commits to disbursing a specific monthly sum post-retirement. This sum can be a fixed amount, like $1,000 per month, or determined through a formula that factors in elements like a percentage of the employee's average income over the last five employment years multiplied by the total years of service.

It's crucial to acknowledge a significant shift in the pension landscape, particularly in the private sector. Over the last few decades, employers have increasingly moved away from traditional defined benefit plans, opting instead for defined contribution plans, exemplified by the popular 401(k). In 1979, 64% of employees with retirement plans relied solely on defined benefit pensions. Fast forward to 2005, and 63% exclusively utilized a 401(k). Regulatory and financial pressures have been instrumental in steering this decline in defined benefit plans, reflecting a clear and consistent trend of diminished importance attributed to these plans by employees.

Studies indicate a noticeable decline in the significance employees place on defined benefit plans. Surveys reveal that a third of employers no longer consider them important, marking a notable increase from a quarter in previous years. Since 2006, there has been a continuous shift from defined benefit to defined contribution plans.

Defined benefit plans are undergoing a phase-out, with changes typically taking a negative turn, such as reductions, freezes, or outright termination. Despite these trends, many public employers still uphold defined benefit plans, often complementing them with defined contribution strategies. This nuanced landscape underscores the evolving nature of retirement benefits in the contemporary employment arena.

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act

The impact of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) on the framework of retirement plans is pivotal. Enacted in 1974, ERISA safeguards the assets of millions of Americans, ensuring that funds invested in retirement plans throughout employees' careers remain accessible post-transition. This federal law establishes minimum standards for retirement plans in private industries, dictating crucial aspects such as the eligibility criteria for employee participation, the timeline for acquiring nonforfeitable interest in plan benefits, and the implications for benefits during an employee's absence from their job. ERISA also delineates the rights of spouses to a portion of an employee's benefits in the event of the employee's death. The majority of ERISA provisions became effective for plan years starting on or after January 1, 1975.

It's important to note that ERISA doesn't mandate employers to establish a retirement plan; rather, it sets forth the minimum standards a plan must meet if established. While ERISA doesn't prescribe specific employee compensation, it does mandate the provision of comprehensive information about retirement plan features and funding to employees. Some information must be regularly and automatically provided, with certain aspects available at no cost and others incurring charges.

ERISA establishes minimum standards for various facets, including participation, vesting, benefit accrual, and funding. It imposes funding rules, compelling plan sponsors to ensure adequate financial support for the plan.

A crucial aspect of ERISA is the accountability it demands from plan fiduciaries. Fiduciaries, defined as individuals exercising discretionary authority or control over a plan's management or assets, bear the responsibility of adhering to established principles of conduct. Failure to do so may render fiduciaries liable for restoring plan losses. ERISA also empowers plan participants with the right to legal recourse, allowing them to sue for benefits and breaches of fiduciary duty. This comprehensive framework underscores ERISA's role in safeguarding the interests and financial security of employees enrolled in retirement plans.

The Retirement Equity Act of 1984

On August 23, 1984, Congress enacted the Retirement Equity Act (REA), a landmark legislation that brought about significant amendments to both the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) and the Internal Revenue Code. The REA introduced a range of pivotal rules with the following key provisions:

Reduction in Minimum Age Requirement: The REA lowered the minimum age for participation in pension plans, expanding access for individuals seeking to engage in retirement programs.

Extension of Vesting Years: The legislation increased the years of service considered for vesting purposes, enhancing the rights of employees in securing their entitled benefits over an extended service period.

Revised Break-in-Service Rules: The REA liberalized the break-in-service rules for vesting purposes, providing greater flexibility and fairness in recognizing continuous service.

Inclusion of Maternity and Paternity Leave: Plans were barred from counting maternity and paternity leave as a break in service for both participation and vesting considerations, acknowledging the importance of family-related leaves.

Mandatory Survivor Benefits: Qualified pension plans were mandated to offer automatic survivor benefits, allowing the waiver of such benefits only with the explicit consent of the employee and their spouse.

Compliance with Domestic Relations Court Orders: The REA clarified that pension plans could adhere to specific domestic relations court orders, enabling them to make payments to an employee's former spouse (or an alternate payee) without violating ERISA's restrictions against the assignment or alienation of benefits.

Expanded Protection of Accrued Benefits: The legislation broadened the definition of accrued benefits safeguarded against reduction, fortifying the security of employees' accumulated retirement assets.

Additionally, the REA introduced minimum participation standards aimed at facilitating swift involvement of eligible employees in retirement plans, curbing age-based exclusions from policy coverage, and safeguarding rehired employees from prolonged periods of nonparticipation resulting from short interruptions.

Moreover, the REA set the minimum age for mandatory participation at 21 years, requiring one full year of credited service. This provision aimed to streamline and enhance the inclusivity of retirement plan eligibility, ensuring a more comprehensive and equitable approach to employee participation.

The calculation of credited service plays a crucial role in determining various aspects related to employee benefits within a qualified retirement plan. Specifically, it is instrumental in assessing:

Participation Eligibility: Credited service is a key factor in determining whether an employee meets the eligibility criteria to participate in a qualified benefits plan.

Vesting Status: It is pivotal in evaluating the vested (nonforfeitable) portion of an employee's benefits, ensuring that accrued benefits are protected and accessible.

Accrued Benefits: Credited service is utilized to compute the benefits accrued by a plan participant over the course of their service.

For the purposes of participation eligibility and vesting, a year of service is defined as the completion of 1,000 or more hours of service during a specific period.

Credited Service

The vested rights of an employee are contingent upon the source of contributions:

Employee Contributions: Rights stemming from an employee's own contributions under a qualified retirement plan must be vested at all times.

Employer Contributions: Benefits attributable to employer contributions must be fully vested when the employee reaches normal retirement age. The acquisition of vested interest in these benefits before normal retirement age follows specific alternative vesting schedules:

10-Year (Cliff-Vesting) Rule: Requires 100% vesting of an employee's accrued benefits, derived from employer contributions, after ten years of service.

5- to 15-Year Graded Vesting Schedule: Mandates that after completing five years of service, the employee earns at least 25% vested interest in the employer's contributions. Vesting increases by 5% each year for the subsequent five years and an additional 10% each year for the subsequent five years, resulting in full vesting within 15 years.

Rule of 45: If an employee has five or more years of service, they must acquire a minimum of 50% vested interest in the accrued benefit derived from employer contributions when the sum of age and service equals or exceeds 45. Additional vesting of 10% occurs for each subsequent year until full vesting is achieved. After ten years of service, benefits must be vested by 50%, irrespective of age, with an additional 10% of vesting for each subsequent year. This comprehensive framework ensures a gradual and equitable vesting progression for employees in alignment with their years of service and age.

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation

ERISA, the federal legislation that oversees employee benefit plans, establishes a safety net for participants through the creation of the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation (PBGC). Instituted in 1974, the PBGC serves as a safeguard for pension benefits within the realm of private-sector defined benefit plans—those plans that traditionally provide a predetermined monthly payout upon an employee's retirement.

In the event of a defined benefit plan termination lacking adequate funding to cover all stipulated benefits, the PBGC steps in with its insurance program. This program bridges the financial gap, compensating individuals up to the legally defined limits. Consequently, most recipients receive the entirety of the benefits they would have accrued before the plan's termination.

The PBGC's financial foundation is multifaceted. It draws from insurance premiums contributed by companies whose plans fall under its protective umbrella, assets of pension plans assumed by the PBGC as a trustee, and recoveries obtained from companies previously responsible for the benefits plans. Notably, the PBGC sustains itself without reliance on taxpayer funding.

An interesting facet of the PBGC's operations lies in its ability to insure plans, even if an employer neglects to fulfill the requisite premium payments. Annual premiums are a key component of this financial structure, with rates determined by factors such as plan type and funding status.

For the year 2014, single-employer plans are subject to a per-participant flat premium rate of $49, a slight increase from the previous year. The variable-rate premium for these plans, dependent on the level of unfunded vested benefits (UVBs), is set at $14 per $1,000 of UVBs—a notable rise from the 2013 rate. This increase is attributed to indexing and a scheduled adjustment. Importantly, the variable-rate premium is capped at $412 times the number of participants.

Conversely, multiemployer plans do not bear the burden of a variable-rate premium. Instead, they adhere to a flat premium rate of $12 per participant, unchanged from the previous year. The intricacies of premium calculations, coupled with the PBGC's role in safeguarding pension benefits, underscore its significance within the framework of ERISA.

The PBGC functions as a governmental insurance entity, with qualified plans remitting premiums for each participant, as detailed in the preceding paragraph. Primarily serving as a last-resort payer for retirement plans, the PBGC steps in when defaults occur due to bankruptcy. Its role mirrors that of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in the banking sector.

The maximum pension benefit guaranteed by the PBGC, mandated by law and subject to annual adjustments, is akin to a safety net for retirees. The PBGC's insurance program for single-employer plans, as reflected in the maximum monthly guarantee tables, illustrates this. For instance, in 2011, individuals retiring at 65 could receive up to $4,653.41 per month, totaling $55,840.92 annually. Actuarial adjustments apply for those retiring at different ages, with lower maximum guarantees for early retirees and higher ones for those retiring later. Notably, benefits adopted within five years before a plan's termination and those not payable throughout a retiree's lifetime do not receive full PBGC guarantees.

In the realm of multi-employer plans, the PBGC's guarantee is based on years of service. For plans concluding after December 21, 2000, it covers 100% of the first $11 monthly payment per year of service and 75% of the subsequent $33. For plans terminating between 1980 and December 21, 2000, the maximum guarantee encompasses 100% of the initial $5 in the monthly benefit accrual rate and 75% of the subsequent $15.

During the fiscal year of 2010, the PBGC disbursed a total of $5.6 billion in benefits to employees affected by failed pension plans. In that period, 147 pension plans faltered, resulting in a 4.5% increase in the PBGC's deficit to a total of $23 billion. The PBGC faces obligations amounting to $102.5 billion, while possessing $79.5 billion in assets. These financial dynamics underscore the critical role played by the PBGC in mitigating the impact of pension plan failures on retirees.

The Nature of Pension Plans

Plan Accounting

Defined Contribution Plans

General Distribution Rules for Defined Contribution (401(k)) Plans

Distribution rules for 401(k) plans hinge on specific events, notably:

Loans from 401(k) Plans

Accounting for Defined Benefits Plans

The Income-Replacement Ratio

What Are Pension Benefit Obligations?

Pension Plan Assets

The Pension Expense