7. Equity-Based Employee Benefit Plans

Objectives of This Chapter:

Introduce Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs):

Provide a comprehensive understanding of ESOPs as a reward mechanism and benefit program for employees.

Explain Tax Issues Related to ESOPs:

Explore the tax implications associated with ESOPs, shedding light on key considerations for both employers and employees.

Discuss Accounting and Reporting Issues Related to ESOPs:

Delve into the accounting and reporting nuances tied to ESOPs, offering insights into the financial aspects of these plans.

Explain the Effect of Fin 46R on Employers’ Accounting for ESOPs:

Illuminate the impact of Fin 46R on how employers account for ESOPs, providing clarity on compliance and reporting standards.

Introduce Employee Stock Purchase Plans (ESPPs) and Design Issues:

Familiarize readers with Employee Stock Purchase Plans and address key design considerations for effective implementation.

Discuss Tax Issues Related to ESPPs:

Examine the tax-related considerations linked to ESPPs, offering a comprehensive overview of the tax landscape for both employers and employees.

Discuss Financing/Accounting Issues Related to ESPPs:

Explore the financing and accounting intricacies associated with ESPPs, providing practical insights into effective management.

Discuss Equity Participation in Pension Plans:

Highlight the role of equity participation in pension plans, elucidating its impact on retirement benefit structures.

Discuss the Tax and Legal Issues of Equity Participation in Pension Plans:

Unpack the tax and legal considerations surrounding equity participation in pension plans, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of regulatory implications.

Explain Issues Related to Stock in 401(k) Plans:

Provide an in-depth examination of issues arising from the incorporation of stock in 401(k) plans, addressing regulatory and operational challenges.

This chapter aims to navigate the intricate landscape of equity participation in employee benefit plans, offering valuable insights into the diverse programs such as Employee Stock Ownership Programs, Employee Stock Purchase Programs, and Equity in Pension Plans. Emphasizing the importance of fairness and compliance, the chapter illuminates the distinct dynamics of these plans while ensuring a comprehensive understanding of their tax, accounting, and legal implications.

Employee Stock Ownership Plans

Various avenues exist for employees to acquire ownership stakes in their employing companies, ranging from stock option plans and stock purchase plans to bonus plans incorporating stock rewards or stock as part of profit-sharing initiatives. However, a pivotal and comprehensive method for employees to engage in such ownership is through participation in an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP).

An ESOP is a retirement plan meticulously crafted to instill employees with an ownership interest in their respective companies. Unlike conventional retirement plans, ESOPs primarily invest in the equity of the sponsoring company. Funded through tax-deductible contributions, which can take the form of stocks or cash, ESOPs operate within a trust framework, overseen by a designated trustee or another named fiduciary. The ESOP must be explicitly identified in the plan's documentation, adhering to specific requirements outlined in the Internal Revenue Code.

In alignment with the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), any individual exercising discretion over the management or administration of a benefit plan, or wielding authority and control over a plan's assets, assumes the role of a fiduciary. The ESOP's trustee, serving as the named fiduciary, can be an individual or a committee specified in the plan's documents responsible for stock investments on behalf of employees. ERISA mandates that plan fiduciaries act prudently and solely in the interest of plan participants. Key responsibilities of an ESOP fiduciary encompass:

Securing Proper Valuation of Stocks:

Undertaking the crucial task of ensuring accurate and fair valuations of the company's stocks within the ESOP framework.

Ensuring Employee Interests Protection in ESOP Transactions:

Safeguarding the interests of employees during various ESOP transactions, fostering a balance between organizational goals and employee welfare.

Approving All Purchases and Sales of the ESOP’s Stock:

Overseeing and approving every transaction involving the purchase and sale of stocks within the ESOP, ensuring transparency and adherence to fiduciary duties.

In essence, an ESOP serves as a dynamic platform for fostering employee ownership, and the fiduciary's role is pivotal in upholding the ethical and legal standards essential for the success and fairness of the plan.

Another pivotal consideration lies in recognizing that an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) stands as a paramount means of aligning the interests of employees with those of management, shareholders, and creditors within the framework of sponsoring companies. ESOPs, distinguished by their tax-exempt status, are meticulously structured employee retirement plans intended primarily to empower employees with an avenue to invest in company stock. The sponsoring entity, in turn, contributes either stock or cash to the ESOP, affording participating employees the opportunity to cultivate an equity stake in their respective companies. As emphasized earlier in this chapter, owing to its nature as an employee benefit program, subjecting it to ERISA's nondiscrimination provisions is imperative.

Delving further into the multifaceted advantages inherent in an Employee Stock Ownership Plan, it is evident that the benefits extend comprehensively to stockholders, the sponsoring company, and the participating employees. Let's elucidate on these benefits in detail.

For stockholders, the merits encompass:

Providing a market avenue for some or all shares of closely held private companies during pivotal owner-related events, including but not limited to retirement, divestiture, and buy-and-sell opportunities for minority shareholders.

Affording majority shareholders the strategic flexibility to divest a portion of their holdings for liquidity while concurrently retaining a controlling interest in the sponsoring company.

Enabling a tax-advantaged ESOP rollover mechanism that allows shareholders to vend stock to the ESOP, thereby deferring capital gains taxes.

The advantages for the sponsoring company are equally compelling:

Leveraging the tax-favored status of ESOPs, the company can utilize pre tax funding for debt servicing.

Tax deductibility of dividends on an ESOP is achievable if directed towards repaying loan principal, which was initially funded through the acquisition of securities. This approach, reducing loan principal with pretax contributions and dividends, results in substantial tax savings, consequently augmenting the company's cash flow.

Substantial empirical evidence underscores the positive impact of ESOPs on employee morale and productivity. By serving as a conduit for workplace democratization, ESOPs are postulated to foster participative management, leading to accelerated growth rates for companies that implement these plans.

For employees, the advantages conferred by an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) are delineated as follows:

Robust Retirement Program: ESOPs stand as a formidable retirement program, ensuring a structured pathway for employees to build a financial cushion for their post-employment years.

Tax-Efficient Accumulation: The accrued value within an employee's ESOP account remains non-taxable as long as it resides within the trust, steadily accumulating and fortifying the employee's financial standing.

Despite its categorization as an employee benefit plan, an ESOP also bears striking resemblances to compensation plans, resembling, in particular, a profit-sharing program.

The procedural facets involve the establishment of a trust fund by the sponsoring company. Subsequently, the company injects shares of its stock or cash funds into the trust, facilitating the acquisition of existing shares. Additional cash contributions from the company are then earmarked for retiring the ESOP's loans, a financial maneuver that carries tax-deductible privileges for the sponsoring company. The shares, securely held in trust by the ESOP, are methodically distributed among employees on a prorated basis.

Crucially, an ESOP mandates the inclusion of a well-defined formula for the annual allocation of employer contributions and forfeitures to individual employee accounts. This allocation hinges on factors such as the employee's compensation during the current plan year, with an option for a combination of compensation and years of service as an alternative distribution plan. Notably, the ceiling for plan years commencing in 2013 is capped at $255,000, subject to adjustments based on future cost-of-living increases. Illustratively, in the calendar year 2013, an employee earning an annual rate of $350,000 would receive an allocation equivalent to that of an employee earning $255,000 within the parameters set by the ESOP.

The Internal Revenue Code establishes annual limits for additions to an ESOP account, comprising the employee's allotted shares from the sponsoring company's contributions and any forfeitures. This cap encompasses contributions to other plans, such as a 401(k). In 2013, the maximum additional amount is the lesser of $51,000 or 100% of an employee's compensation.

Vesting in the plan occurs over time as employee account balances grow. Full vesting typically occurs within three to six years, regardless of whether it follows a cliff (all-at-once) or gradual vesting structure.

Upon an employee's departure from the sponsoring company, the company generally repurchases any shares, particularly if no public market exists. Consequently, a private company must undergo an annual business valuation. This valuation, conducted by an independent appraiser, appraises the company stock in the ESOP annually and whenever the ESOP acquires stock from the company, an employee, an officer, a director, or a shareholder holding 10% or more of the company.

The Department of Labor (DOL) and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) have provided explicit guidance outlining the essential considerations for appraising a company and specifying the qualifications of the appraiser.

A qualified appraiser must publicly present themselves as proficient in making regular appraisals of the same type of property, maintaining independence from the company and other parties involved in the ESOP transaction.

The IRS and DOL place significant weight on the credibility of an appraiser's fair market value (FMV) conclusions and their independence. To meet these standards, the valuation cannot be conducted by:

The taxpayer overseeing the ESOP

A party involved in the ESOP transaction where the relevant property is acquired

An employee of the taxpayer overseeing the ESOP

An individual or firm consistently engaged by the taxpayer to manage the ESOP, provided the majority of their appraisals are not for entities other than that taxpayer.

Valuation of company stock held by an ESOP must occur at least annually, typically at the close of the sponsor's fiscal year. In the case of stock transactions, where the ESOP is buying or selling, the valuation must take place at the transaction date.

In the realm of private companies, there exists some flexibility regarding the voting rights of employee shareholders. Conversely, in public companies, these voting rights align with those of any other shareholder.

The disbursement of benefits from an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) can take the form of cash or company stock. Participants in the program are entitled to request a distribution of their account balances in stock, unless official company documentation limits stock ownership by active employees or the company operates as an S corporation. In such cases, the ESOP has the option to distribute either cash or company stock, the latter of which must be promptly resold to the company. Benefit distributions may occur either as a lump sum or in installments, with the minimum distribution period for installments not exceeding five years.

An ESOP can be deployed in various ways, including the implementation of a leveraged ESOP. In this scenario, the ESOP borrows funds to acquire shares of the employer's stock. The loan may originate from a bank or financial institution, or the selling shareholder might finance the transaction by retaining a note for part or the entire purchase price. Typically, the ESOP loan is secured by assets from the sponsoring company. In certain instances, the shareholder may be required to guarantee the loan or provide security for its repayment. The ESOP stands out as the sole type of employee benefit plan empowered to utilize the company's credit and the credit of its shareholders to facilitate the acquisition of company stock. The program utilizes the cash proceeds from the loan to purchase stock, with annual cash contributions from the sponsoring company applied to repay the loans' principal and interest.

As debt obligations are fulfilled, shares are liberated from a suspense account and distributed to individual employees' accounts. Typically, the Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) secures funds for debt repayment through employer contributions and dividends on the employer's stock.

ESOPs serve as a potent mechanism to both inspire and reward participating employees. A company can issue Treasury shares to the ESOP, deducting their value (up to 25% of covered pay) from taxable income. Alternatively, a company may contribute cash to purchase shares from existing public and private owners. In some instances, ESOPs are integrated with employee savings plans, such as 401(k) plans. Instead of matching savings with cash, the sponsoring company matches employee contributions with shares from the ESOP. This not only incentivizes employee participation but also serves as a substantial surrogate for a retirement program, ensuring adequate income security during an employee's retirement years.

In specific scenarios, ESOPs function as a market for shares, such as when owners depart from successful closely held companies, when there's no successor for a family-owned company, or when family owners seek to diversify their portfolios. Moreover, ESOPs can facilitate management in an internal buyout of shareholders and function as an acquisition vehicle for complementary businesses. This flexibility underscores the versatility of ESOPs in addressing various corporate needs and objectives.

Refinancing existing corporate debt with an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) offers a strategic avenue to enhance after-tax cash flow for the sponsoring company. This refinancing involves providing a loan to the ESOP, utilizing borrowed funds to acquire newly issued company stock. Subsequently, the company employs these resources to retire existing debt, effectively substituting it with the ESOP's debt. Following the refinancing, any company contributions directed toward the principal of the ESOP's debt become tax-deductible, a contrast to the primary payments on the preceding corporate debt.

An additional facet of the ESOP's advantages pertains to various tax benefits:

Sponsoring companies can secure a tax deduction for their stock contributions to the program, providing a cash flow advantage. However, this comes with the trade-off of dilution in the ownership of existing shareholders.

Cash contributions made by the sponsoring company to the ESOP also qualify for a tax deduction. The plan can leverage these cash contributions to acquire shares or bolster the plan's cash reserves.

When money is borrowed to acquire company shares and subsequently repay the loan principal and interest, the repayment amounts become tax-deductible. Consequently, the financing structure of an ESOP offers pre-tax benefits. Previously, under tax laws, only 50% of the interest income from an ESOP's loans used to purchase the sponsoring company's stock was taxable. This exception now applies exclusively when the ESOP holds the majority of the company's stock. Loan terms are capped at 15 years, creating an opportunity to borrow at reduced rates and prompting the utilization of ESOPs as a mechanism for executing leveraged buyouts.

In C corporations, the reinvestment of ESOP shares in other securities becomes a viable option, allowing the deferral of taxes on any gain if the ESOP holds a substantial 30% ownership stake in the sponsoring company. Furthermore, when a C Corporation sells stock to an ESOP, the seller can defer income taxes on the gain by leveraging the benefits provided under Section 1042 of the Internal Revenue Code.

Dividends disbursed on an ESOP's stock can be deducted by the sponsoring company, provided these dividends are paid in cash to the plan's participants within 90 days after the close of the current plan year. Alternatively, these dividends may be utilized to fulfill payments on a loan incurred for the acquisition of qualifying employer securities.

In the case of an ESOP being the proprietor of stock in an S Corporation, all income allocated to the ESOP—based on its percentage ownership—remains tax-free, given the ESOP's status as a tax-exempt entity. Consequently, stock owned by the ESOP is not subject to federal income tax, and it often enjoys exemption at the state level. Furthermore, an S Corporation wholly owned by an ESOP incurs no income tax on its profits.

Employees contributing to an ESOP on their own behalf experience a tax-free contribution process. Taxes are only triggered upon distributions from their accounts, occurring as and when these distributions take place. Typically, when employees receive distributions, they benefit from favorable tax treatments. Opting for a rollover into an IRA or another tax-deferred retirement plan allows employees to maintain tax advantages. Alternatively, individuals may choose to pay current taxes on their distributions, potentially making them eligible for capital gains tax benefits.

ESOP and Accounting Issues

SOP-76-3, titled "Accounting Practices for Certain Employee Stock Ownership Plans," emerged in December 1976 as a pivotal response to accounting and reporting challenges confronting sponsoring employers with leveraged ESOPs. At the time of its issuance, SOP-76-3 became the primary guidance source, providing essential clarity on intricate matters.

Recording of ESOP Obligations: The SOP mandated that ESOP obligations guaranteed by the sponsor be recorded as financial statement liabilities, establishing a crucial foundation for transparent accounting.

Recognition of Employer Contributions: Employer contributions or commitments to make such contributions were directed to be recognized as interest and compensation expenses, ensuring a comprehensive reflection of financial commitments.

Treatment of ESOP Shares for Earnings per Share Calculation: A significant directive in SOP-76-3 stipulated that, for the purpose of calculating earnings per share, all company shares held by the ESOP should be treated as outstanding, aligning accounting practices with the economic realities of ownership.

Dividend Treatment: SOP-76-3 mandated that all dividends paid on shares held by an ESOP should be charged to retained earnings, a decision made in contrast to arguments suggesting that certain dividends might represent compensation or interest expenses when paid to an ESOP.

Subsequent to the issuance of SOP-76-3, congressional laws governing ESOPs underwent multiple revisions. The IRS and the U.S. Department of Labor introduced various regulations, prompting changes in ESOP operational methods and underlying motivations for establishment.

Despite the clarity provided by SOP-76-3, accounting controversies persisted over the years, particularly regarding the measurement of costs for compensation and the treatment of dividends distributed through ESOP-held shares. The evolving landscape of ESOP structures and purposes, coupled with changes in laws and regulations, underscored the limitations of SOP-76-3.

Recognizing the need for a comprehensive reassessment, the Accounting Standards Executive Committee (AcSEC) of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) initiated a project to reconsider SOP-76-3 and address other ESOP-related issues not explicitly covered in existing accounting literature.

SOP-76-3, a landmark in ESOP accounting, played a crucial role in shaping practices. However, the dynamic nature of ESOPs and the regulatory environment necessitated ongoing scrutiny. The AcSEC's commitment to revisiting these matters demonstrates a proactive approach to evolving accounting standards, ensuring continued relevance in the ever-changing landscape of employee stock ownership plans.

The subsequent sections delve into these accounting intricacies within the distinctive framework of ESOPs, elaborating on concepts previously introduced in this chapter.

Non leveraged ESOPs

AICPA Statement of Position (SOP) 93-6, issued by the AcSEC, provides comprehensive guidelines for Employers' Accounting for Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs), addressing both leveraged and non leveraged structures. Within this framework, a non leveraged ESOP is distinctly characterized, as outlined below:

A non leveraged ESOP, as defined by SOP 93-6, necessitates periodic contributions by the employer in the form of stock or cash on behalf of plan participants. These contributions, comprising outstanding shares, treasury shares, or newly issued shares, are allocated to employee accounts and securely held by the program until distribution at a predetermined future event, such as retirement or termination from employment.

Functioning as a defined contribution plan, a non leveraged ESOP adheres to the guidelines set forth in FASB Statement No. 87, Employers’ Accounting for Pensions. The accounting principles for defined contribution plans are conceptually straightforward: the employer records the cost of the contribution in the year it is earned, aligning with the period during which employees provide services that warrant compensation, even if the actual contribution occurs in a subsequent year.

In the case of a non leveraged ESOP, the employer is afforded the flexibility to contribute either shares (Treasury or newly issued) or cash to the program. When cash is chosen, the ESOP's trustee utilizes the funding to acquire shares from the open market or directly from the employer. Whether contributed or purchased, these shares are allocated to employees' accounts by the end of the ESOP's fiscal year. In instances where cash is utilized, the compensation cost is measured by the cash amount contributed. Conversely, if stock is contributed, the fair value of the shares becomes the basis for measuring the compensation cost. This measurement remains consistent irrespective of whether the shares are newly issued or sourced from Treasury. Such a nuanced approach ensures a comprehensive and transparent accounting methodology for non leveraged ESOPs under SOP 93-6.

Leveraged ESOPs

SOP 93-6, effective for fiscal years commencing after December 15, 1993, instituted mandatory accounting standards for shares purchased by leveraged ESOPs post December 31, 1992. In the context of leveraged ESOPs, which secure funds by borrowing to acquire shares from sponsoring companies, the borrowing can occur directly from the employer or from external sources.

When the ESOP borrows directly from the sponsoring employer, the terms of the loan may align closely with those from alternative external sources. In cases where the ESOP secures funds externally, it's customary for the employer to guarantee the loan. Leveraged ESOPs have the flexibility to acquire shares, whether newly issued or from the company's treasury, directly or through open market transactions. Two primary sources fund debt servicing: employer contributions and dividends yielded from the ESOP's shares.

The ESOP initiates its program by holding shares in a suspense account, serving as collateral for the ESOP's loan. These shares, termed "suspense shares," are released from the suspense account as the ESOP fulfills its debt obligations, subsequently becoming available for allocation to employees' accounts. It is imperative that these released shares are allocated to individual employee accounts by the conclusion of the fiscal year.

In instances where dividends on allocated shares are utilized to service debt, employees holding these shares are entitled to receive an allocation of shares with a fair value. This dual-purpose approach not only facilitates debt repayment but also ensures equitable distribution of benefits to employees based on the value of their allocated shares. By adhering to these guidelines, SOP 93-6 establishes a robust framework for transparent and accountable accounting practices within leveraged ESOPs.

Purchase of Shares by ESOPs

A sponsoring employer must expeditiously document any issuance of shares or the sale of Treasury shares to an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) as these transactions unfold. Simultaneously, there is a critical obligation to report the associated charge linked to unearned ESOP shares in a dedicated contra-equity account. This contra-equity account, having its own distinct presentation on the company's balance sheet, ensures a clear and segregated representation of the financial impact stemming from ESOP-related activities.

Even in scenarios where a leveraged ESOP acquires outstanding shares of its sponsoring employer's stock from the open market, deviating from a direct purchase from the employer, precision in reporting remains paramount. The consistent practice dictates the application of the unearned ESOP shares charge, accompanied by a corresponding credit entry to either cash or debt. The choice between cash or debt is contingent upon whether the ESOP is internally or externally leveraged, thereby reflecting a meticulous and context-specific approach to accounting.

By upholding these rigorous reporting standards, sponsoring employers not only fulfill their reporting obligations but also contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the ESOP's financial implications within the company's equity structure. The segregated presentation of the contra-equity account on the balance sheet underscores a commitment to transparency, offering stakeholders a granular insight into the distinct financial dynamics associated with the ESOP. This approach aligns with best practices, bolstering confidence in the accuracy and integrity of the company's financial reporting, particularly in the context of ESOP-related transactions.

Release of ESOP Shares

SOP 93-6 intricately acknowledges the nuanced dynamics surrounding the release of ESOP shares from a suspense account, attributing such releases to various circumstances, including direct employee compensation, liability settlements on behalf of the employer for other benefits, and the replenishment of dividends on allocated shares earmarked for debt service.

Given the committed nature of ESOP share releases, the appropriate accounting treatment involves crediting unearned ESOP shares. Depending on the purpose of the release, the associated charge should be directed towards compensation costs, dividends payable, or compensation liabilities. Importantly, regardless of the chosen account, the amount charged must be grounded in the fair value of the shares pledged to be released.

A pivotal shift introduced by SOP 93-6, diverging from SOP 76-3, lies in the timing of measuring compensation. The alteration in focus is from the date of ESOP share acquisition to the crucial juncture when the shares are committed to be released from the suspense account, becoming accessible for employee accounts. This adjustment recognizes the prevalent practice among leveraged ESOPs, which typically service debt annually, often coinciding with the end of the plan's fiscal year, effecting the release of shares from the suspense account.

The concept of "committed-to-be-released" emerged as a logical solution, ensuring that compensation is recognized throughout the year in alignment with the continual provision of services by employees. This proactive approach accommodates the commitment of the sponsoring employer to fund the program and fulfill contractual obligations to service debts, effectively pledging shares in exchange for employee services, albeit with legal release occurring at the year's end.

For accounting purposes, this methodology treats the shares as if they are released continuously, resulting in the ratably recorded compensation expense across all quarters. Importantly, the continual measurement of compensation results in an average fair value, a departure from measuring value solely based on the release date, highlighting the adaptive and nuanced approach taken to address the unique circumstances of ESOPs under SOP 93-6.

Direct Compensation

Certain employers institute Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) independent of any other benefit or compensation commitments. In this context, the shares within the program serve as direct compensation for their workforce. To facilitate this compensation structure, the sponsoring employer must acknowledge and recognize a compensation cost equivalent to the fair value of the shares.

In this scenario, ESOP shares are typically considered committed to be released incrementally throughout the accounting period as employees fulfill their services. The recognition of compensation cost is aligned with this committed-to-be-released concept, utilizing average fair values to determine the cost of compensation during each reporting period, whether annual or interim.

To elaborate, the fair value of the shares is deemed committed to be released in a proportional manner over the accounting period, reflecting the ongoing provision of services by employees. This approach ensures a consistent and equitable recognition of compensation cost, maintaining fidelity to the committed-to-be-released principle.

Importantly, once the cost is recognized in a specific period, subsequent adjustments are not made for any changes in the fair value that may occur in subsequent periods. This provides a stable and predictable accounting framework, with the employer acknowledging the fair value at the time of recognition and maintaining that valuation throughout the reporting periods. This unadjusted approach underscores the employer's commitment to transparent and consistent financial reporting within the parameters of ESOPs structured as direct compensation to employees.

Liability for Other Employee Benefits

In instances where employers commit to providing specific benefits, such as contributions to a 401(k) or a profit-sharing plan based on a predetermined formula, some opt to leverage their Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) to either partially or fully fund these benefits. In the accounting treatment of these benefits, employers are advised to recognize costs and liabilities in alignment with the same method they would employ if the ESOP were not utilized as a funding mechanism.

For ESOP shares to effectively settle liabilities associated with these benefits, employers should report the satisfaction of liabilities precisely when the shares are committed to be released for this purpose. The determination of the number of shares released to settle the liability is contingent upon their fair value as of the specific dates stipulated by the employer, typically outlined in the ESOP's documentation.

This approach ensures a consistent and equitable accounting methodology, wherein the employer acknowledges the costs and liabilities associated with providing benefits to employees, adhering to established principles irrespective of the vehicle used for funding. The commitment to reporting the satisfaction of liabilities at the point when ESOP shares are committed to be released reflects a transparent and responsible accounting practice. By referencing the fair value on specified dates, employers ensure accuracy and precision in recognizing the financial impact of utilizing ESOP shares to fulfill obligations related to employee benefits.

Replacing Dividends on Allocated Shares

The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) grants employers the authority to utilize dividends on allocated ESOP shares for debt service, provided that the fair value of the allocated shares is not less than the amount of dividends used for this purpose. In cases where shares released encompass those earmarked to replace dividends on previously allocated shares utilized for debt service, employers are advised to report the settlement of the dividend payable precisely when the shares are committed to be released for this replacement.

To execute this reporting, the employer considers the number of shares committed to be released, strategically aligning with the fair value as of the specified dates outlined in the ESOP documents. These dates are typically delineated based on the employer's interpretation of current IRS regulations, reflecting a proactive approach to compliance and transparency.

By adhering to these guidelines, employers ensure a compliant and accountable utilization of dividends on ESOP shares, in accordance with both regulatory standards and the employer's specified commitment to financial transparency. This methodical and forward-looking approach not only aligns with IRS regulations but also reflects a responsible and diligent stance in managing the financial intricacies associated with ESOPs.

Account for Released Shares

As ESOP shares are slated to be released, the corresponding accounting treatment necessitates the crediting of unearned shares, determined by the cost of these shares to the ESOP. Employers are duty-bound to apply a charge or credit equivalent to the disparity between this cost and the fair value of the shares to shareholders' equity, mirroring the familiar approach employed for gains and losses on treasury stock sales—typically directed to additional paid-in capital.

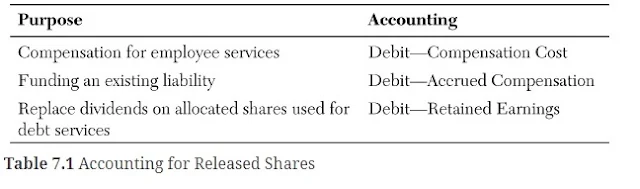

The specific debit entry is contingent upon the intended purpose for which the shares are released, as meticulously outlined in Table 7.1. This targeted approach ensures a granular and purpose-driven accounting methodology, aligning with the distinct objectives behind the release of ESOP shares.

In essence, this comprehensive accounting framework not only upholds transparency but also draws parallels with established accounting practices, demonstrating a methodical and consistent treatment of ESOP-related transactions. By integrating the principles akin to treasury stock transactions, employers can effectively navigate the complexities associated with ESOP shares, ensuring accurate financial representation and compliance with prevailing accounting standards.

Fair Value

Irrespective of the account charged, it is imperative that the amount of the charge aligns with the fair value of the committed-to-be-released shares. SOP 93-6 stipulates that the fair value of an ESOP share is the amount the seller could reasonably expect in a current sale between a willing buyer and a willing seller, excluding forced or liquidation scenarios. In the case of traded shares, the price in the most active market should serve as the measure for fair value.

When no market price is readily available, the employer is tasked with providing its own best estimate of fair value. In instances where precision is crucial, the engagement of independent experts may be necessary for a reliable estimate. Recent independent stock valuation reports, conducted within twelve months of the employer's year-end, can contribute to determining the best estimate of fair value.

Theoretically, fair value should be assessed on a daily basis, but for practical reasons, most employers opt for the average fair value over a specific period. It's essential to note that utilizing the fair value determined on the last day of the year would be inappropriate.

Given that compensation expense under SOP 93-6 is susceptible to fluctuations based on the fair value of shares, the resulting charge to compensation may exhibit volatility. To mitigate this, introducing flexibility into the terms of the ESOP becomes pivotal. This could involve structuring the ESOP terms to allow adjustments in the amount repaid and the number of shares released annually. For instance, a debt structure with a lengthy stated life and minimal annual payments, coupled with the option for unlimited prepayment without penalties, provides a mechanism for reducing volatility. This flexible approach promotes stability and aligns with best practices in managing the financial implications of ESOPs.

Dividends on ESOP Shares

Due to employers exercising control over the use of dividends on unallocated shares, these dividends are categorized as such for financial reporting purposes. When these dividends are utilized to service debt, it is crucial to report them explicitly as a reduction of debt or accrued interest payable. This meticulous reporting ensures accurate representation and transparency in financial statements.

In cases where dividends on unallocated shares are distributed to employees and added to their accounts, the appropriate reporting treatment is to recognize them as a compensation cost. This aligns with sound accounting principles and provides a clear depiction of the financial impact of these dividends on employee compensation.

Conversely, dividends on allocated shares are appropriately charged to retained earnings. The satisfaction of these dividends can take various forms, including contributing cash funds to employees' accounts, contributing additional shares to their accounts, or releasing shares from the ESOP's suspense account directly to employee accounts. This comprehensive reporting approach not only aligns with accounting standards but also reflects the diversity in ways dividends on allocated shares can be fulfilled.

In essence, this robust reporting framework ensures a thorough and accurate representation of the utilization and impact of dividends within the context of ESOPs, contributing to transparency and accountability in financial reporting.

Reporting of Debt and Interest

In the context of applying SOP 93-6, the characterization of ESOP debt encompasses three distinct types:

Direct Loan:

Definition: A loan extended by a lender other than the sponsoring employer directly to the ESOP. Often, such loans involve a formal guarantee or commitment by the employer.

Reporting Obligation: Employers sponsoring a direct-loan ESOP are obligated to recognize the resulting ESOP obligations to the outside lender as liabilities. Additionally, they should accrue interest costs on the debt and report cash payments to the ESOP for debt service. This holds true whether the source of cash is derived from employer contributions or dividends.

Indirect Loan:

Definition: A loan from the employer to the ESOP, accompanied by a related external loan to the employer.

Terminology: ESOPs utilizing indirect loans are commonly referred to as being internally leveraged.

Employer Loan:

Definition: A loan directly made by the employer to the ESOP, devoid of any related external loan.

Reporting Perspective: Employers sponsoring an ESOP with an employer loan should not depict the ESOP's note payable or the employer's note as receivable on their balance sheets. Consequently, recognition of interest costs or income on such a loan is not warranted.

For employers sponsoring a direct-loan ESOP, it is crucial to report external loans as liabilities, refraining from recognizing a loan receivable from the ESOP as an asset. Instead, they should accrue interest costs on the external loan, accounting for loan payments as reductions of principal and accrued interest payable. Contributions to the ESOP and simultaneous payments from the ESOP to the employer for debt service should not find a place in the employer's financial statements.

The distinction in reporting for each type of ESOP debt ensures clarity and adherence to accounting standards, reflecting the nuances associated with the varied structures of ESOP financing.

Effect of FIN 46R on Employers’ Accounting (ESOPs)

FASB Interpretation (FIN) No. 46-R, focusing on the consolidation of Variable Interest Entities (VIEs), delineates guidelines for determining when an entity meeting certain conditions—termed a variable interest entity (VIE)—should be consolidated by a company, irrespective of lacking a majority voting interest. According to FIN 46-R, the entity with the controlling financial interest in a VIE is either the party obligated to absorb a majority of the entity’s anticipated losses or, in its absence, the entity entitled to receive a majority of the VIE’s expected residual returns.

Paragraph 4(b) of FIN 46-R explicitly specifies that an employer should refrain from consolidating any benefit plan governed by FASB Statement No. 87, Employers’ Accounting for Pensions. As nonleveraged ESOPs fall under the purview of Statement No. 87, the provisions outlined in FIN 46-R do not apply to them.

However, leveraged ESOPs, not being subject to the provisions of Statement No. 87, necessitate the application of FIN 46-R to ascertain potential consolidation requirements. In instances where an ESOP's trust is deemed a VIE, and the employer has guaranteed a third-party lender's loan directly to the ESOP or borrowed funds directly and subsequently loaned them to the ESOP, it is highly probable that the employer would be identified as the primary beneficiary of the ESOP's trust, as defined in FIN 46-R. This determination holds even if the ESOP has directly borrowed from a third-party lender without the employer initially providing a guarantee for the ESOP's debt.

As emphasized in SOP 93-6, a leveraged ESOPs ability to service its debt relies on the employer's capacity to make contributions or pay dividends in the future. Although the ESOP could theoretically sell shares to meet debt obligations, this approach contradicts the fundamental purpose behind the ESOP's formation. Consequently, the implicit guarantee of the program's financing by the employer becomes evident, aligning with the intended structure of the arrangement. This interpretation underscores the critical role of FIN 46-R in determining consolidation requirements for leveraged ESOPs, ensuring comprehensive and accurate financial reporting.

Disclosures

Employers sponsoring an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) should provide comprehensive and transparent disclosures regarding the plan. The disclosure should include the following information, as applicable:

Plan Description:

A detailed description of the ESOP, encompassing the basis for determining contributions, covered groups, and significant matters influencing how information is compared across all presented periods.

For leveraged ESOPs and pension-reversion ESOPs, this description should explicitly outline the basis for share release, dividend allocation methods, and the utilization of unallocated shares.

Accounting Policies:

A clear depiction of the accounting policies employed for ESOP transactions, including methods for measuring compensation, classification of dividends on ESOP shares, and implications for earnings per share (EPS) computations.

If the employer deals with both old ESOP shares (not subject to SOP 93-6 guidance) and new shares (where SOP 93-6 is applicable), the accounting policies for both sets of shares should be delineated.

Compensation Costs:

The disclosure of the total compensation costs recognized during the specified reporting period.

Shares Information:

The number of allocated shares, committed-to-be-released shares, and suspense account shares held by the ESOP as of the balance sheet date.

Separate presentation for shares accounted for under SOP 93-6 and grandfathered ESOP shares.

Fair Value of Unearned Shares:

The fair value of unearned shares at the balance sheet date, specifically accounted for under SOP 93-6. No such disclosure is required for old shares not subject to SOP 93-6 guidance.

Repurchase Obligation:

The disclosure of the existence and nature of any repurchase obligation associated with the ESOP.

Including information on the fair value of shares allocated as of the balance sheet date that is subject to repurchase obligation.

These disclosures collectively contribute to a thorough understanding of the ESOP structure, accounting treatments, and potential financial obligations. By providing this information, employers enhance transparency, aiding stakeholders in making informed assessments of the ESOP's financial impact and the employer's commitment to the program.

Employee Stock Purchase Plans

An Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP) is meticulously crafted to meet the qualification criteria outlined in Section 423 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). The fundamental objective behind establishing such a plan is to foster widespread employee ownership of the company's stock. The ESPP serves as a mechanism to encourage broad-based participation, enabling employees to become stakeholders in the success and growth of the company they work for. This alignment of interests not only enhances employee engagement but also reinforces a sense of ownership and shared success within the workforce.

A publicly traded company has the option to institute an Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP), designed to empower its employees to regularly acquire limited amounts of the company's stock. This purchase is facilitated at a discount of up to 15% (and occasionally higher) of the stock's fair market value. Importantly, employees incur no federal income tax liability on either the discount or any subsequent appreciation until the point of selling their shares. Notably, this sale may transpire while the employee is subject to federal income taxes, typically at the long-term capital gains rate.

From an accounting perspective, a company generally does not trigger a compensation charge under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in connection with an ESPP. Whether the company receives a federal income tax deduction for the portion of the employee's gain represented by the discount hinges on the timing of the employee's stock sale.

Key features of an ESPP include the ability for the discount to be up to 15% of the lower fair market value at either the offering commencement date or the actual purchase date. This flexibility is commonly referred to as a "look-back feature." While ESPPs are not obliged to incorporate a look-back feature, many opt for the maximum discount and the associated look-back provision.

Section 423 of the Internal Revenue Code establishes the fundamental operational parameters for an ESPP. In a typical program structure, employees are granted the option to purchase company stock at an advantageous price at the conclusion of a predefined offering period. Although Section 423 does not mandate that shares must be acquired through payroll deductions, many employers find this method administratively simpler compared to having plan participants pay for the stock on the same day. Overall, an ESPP serves as a powerful tool to foster employee ownership and engagement in the company's financial success.

An Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP) functions by allowing employees to opt into the plan, choosing to have a specific amount or percentage of their salary or wages (typically ranging from 1% to 10%) deducted from each payroll on an after-tax basis. Throughout the offering period, the sponsoring company deducts these amounts from the employees' compensation, allocating them to individual employee accounts dedicated to the ESPP. These payroll deductions are conceptually accumulated, not held in a separate trust, and usually do not accrue interest during the offering period, which typically spans six to 12 months, with the possibility of extending to a maximum of 27 months. At the conclusion of the offering period or at multiple purchase dates within that period, the accumulated funds for each employee are utilized to acquire employer stock.

Before the commencement of each offering period, eligible employees declare their intention to participate in the plan. Subsequently, participants complete a subscription agreement or enrollment form, specifying the percentage or dollar amount to be deducted from their paycheck throughout the offering period.

In most instances, the purchase price is established at a discount to the Fair Market Value (FMV) of the company's shares. While some plans apply the discount to the FMV on the purchase date (e.g., 85% of the FMV on that specific date), it is more customary for the program to calculate the discount based on the stock's value on the first day or the last day of the offering period, opting for the lower of the two values. This approach ensures fairness and consistency in applying the discount across participants.

Let's illustrate this process with a concrete example:

Imagine UMB Corp., a hypothetical corporation, sponsors an Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP) featuring a look-back feature and a generous 15% discount. The program's offering commencement dates are January 1 and July 1, while the purchase dates are June 30 and December 31. For this example, consider an employee earning $40,000 annually, opting to have 5% of their pay withheld on an after-tax basis from each paycheck.

January 1 to June 30, 2012:

Total withheld: $1,000 ($40,000 * 5% * 6 months).

Stock price on January 1, 2012: $25 per share.

Calculation: $1,000 divided by 85% of $25 (the lower of the stock prices on January 1, 2012, or June 30, 2012).

Result: By June 30, 2012, the employee purchases 47 shares of UMB Corp.'s stock.

July 1 to December 31, 2012:

Total withheld: Another $1,000.

Stock price on July 1, 2012: $35 per share.

Calculation: $1,000 divided by 85% of $35 (the lower of the stock prices on July 1, 2012, or December 31, 2012).

Result: By December 31, 2012, the employee purchases an additional 42 shares of UMB Corp.'s stock.

In both scenarios, the lower end of the stock price is used for calculation, ensuring fairness and consistency in applying the 15% discount. This example showcases how the ESPP operates, providing employees with an opportunity to accumulate shares at a discounted rate over distinct offering periods and purchase dates.

Most ESPPs afford employees the option to withdraw from the plan before the exercise date, typically the last day of the offering period. In the absence of withdrawal, the accumulated amounts in their accounts are automatically applied to purchase shares on the exercise date, securing the maximum number of shares at the designated option price. The purchase transactions within ESPPs are commonly facilitated through a transfer agent representing the company or a designated brokerage account.

The initial subscription agreement, delineating the payroll deduction percentage, typically endures for as long as the plan remains in effect. This persists unless the employee chooses to withdraw from the plan, becomes ineligible to participate, or terminates employment with the company. Additionally, many plans grant employees the flexibility to adjust their payroll deduction percentage at any point during the offering period.

To qualify under Section 423 of the Internal Revenue Code, ESPPs must adhere to specific requirements, including but not limited to:

Eligibility Criteria: ESPPs must extend eligibility to a broad spectrum of employees, avoiding exclusivity.

Participation Limits: The Code imposes restrictions on the maximum value of shares an employee can purchase under the ESPP, ensuring a balanced and equitable distribution.

Offering Periods: ESPPs must define specific offering periods during which employees can elect to participate.

Option Price: The option price at which employees can purchase shares must align with the fair market value, often at a discount, as determined by the plan terms.

Stockholder Approval: Stockholder approval is generally required for the establishment of an ESPP or any significant modifications to its terms.

By complying with these requirements, ESPPs can maintain their qualified status under Section 423, ensuring favorable tax treatment for participating employees.

To ensure compliance with Section 423 of the Internal Revenue Code and maintain the qualified status of an Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP), certain key provisions must be observed:

Inclusive Eligibility: All eligible employees should have the opportunity to participate in the ESPP. However, specific exclusions may be made for certain categories of employees, including:

Those employed for less than two years.

Employees with customary employment of 20 hours per week or less.

Employees with customary employment of five months per year or less.

Highly compensated employees as defined by Section 414(q) of the IRC.

All eligible employees should have equal rights under the ESPP, with the provision that the amount of stocks available for purchase may be proportional to compensation. Affiliated group corporations are treated separately, allowing a parent company to extend participation to subsidiaries without a mandatory requirement.

Shareholder Approval: The ESPP must receive approval from shareholders within 12 months before or after adoption by the Board. Provisions requiring shareholder approval under the IRC include:

Total number of shares to be issued under the plan.

Eligibility of corporations within the affiliated group.

Classes of eligible employees, including permissible exclusions.

Shareholder approval typically requires only a majority of a quorum, unless state law, stock exchange rules, or the company's bylaws impose more stringent requirements. It's important to note that implementing an ESPP before shareholder approval, or subjecting it to approval before the first purchase, may risk the need for a charge to earnings under GAAP if the company's stock value increases between the plan's effective date and the shareholders' approval date. Therefore, such a practice is generally considered undesirable.

To adhere to the regulations set forth in Section 423 of the Internal Revenue Code and maintain the qualified status of an Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP), specific provisions must be carefully observed:

Ownership Limitation: Employees owning 5% or more of the stock of the plan sponsor are ineligible to participate in the ESPP.

Equal Rights and Privileges: All ESPP-eligible employees must have access to the same rights and privileges under the plan. Differences in the amount of stock that can be purchased may be based on compensation variations, such as a percentage of compensation.

Grant Requirements:

An employee must be employed at the option's grant date.

Nonemployee directors and independent contractors are typically ineligible for an ESPP.

Employees of parent or subsidiary companies holding 50% or more ownership by the plan sponsor are generally treated as employees of the sponsor for eligibility determination.

Purchase Price Limitation: The purchase price for ESPP stock must not be less than the lesser of:

85% of the Fair Market Value (FMV) of the stock on the date of grant.

85% of the FMV of the stock on the date of exercise.

Non-Transferability: The employee's right to purchase stock under the plan must not be transferable during the employee's life, including to family members or as a gift.

Individual Limitation: The total value of stock available to any individual employee, in any single offering period, may not exceed $25,000. This is based on the stock value at the offering commencement date, regardless of whether the purchase occurs at a price determined concerning the offering commencement date or the exercise date.

To adhere to the regulations outlined in Section 423 of the Internal Revenue Code and maintain the qualified status of an Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP), several critical provisions must be considered:

Purchase Timeframe:

Stock cannot be purchased more than 27 months after the offering's commencement date.

Purchase can extend up to five years from the commencement date if the purchase price, before discount subtraction, is linked to the Fair Market Value (FMV) discount at the purchase date rather than the offering commencement date.

Employee Eligibility and Holding Period:

The employee must have been continuously employed by the corporation up to a date no more than three months (12 months in the case of disability) before the purchase date.

Holding period requirements stipulate that for favorable tax treatment, shares purchased under an ESPP must not be disposed of earlier than two years after the offering commencement date or one year after the purchase date.

Transferability:

An employee's right to purchase stock under the ESPP may not be transferred, except by will or laws of descent and distribution. The right is exercisable during the employee's life only by the employee.

Flexibility in plan design under Section 423 includes:

No Specific Limit on Shares: There is no explicit limit on the number of shares issued under an ESPP. The number of shares reserved considers factors such as the value of the stock, duration of the offering period, limits on employee contributions, eligibility requirements, and more. Employers commonly reserve about 1% to 8.5% of outstanding shares for their ESPPs, with an average around 3.5%.

Evergreen Provision: Some employers incorporate an evergreen, or automatic, stock-replenishment provision in their ESPPs. This provision automatically increases the number of available shares for issuance under the plan, typically every plan year, based on a predetermined percentage of the employer's outstanding shares. The evergreen provision eliminates the need for continual shareholder approval for plan share increases.

Some employers implement measures to regulate the utilization of their Employee Stock Purchase Plans (ESPPs) by imposing restrictions on the number of shares issued in a single offering period. This strategic approach enables employers to effectively plan for potential increases in shares and ensures compliance with shareholder approval requirements.

Apart from the quantity of shares within the plan, the dilutive impact of an ESPP is primarily influenced by two key factors: the stock's purchase price and the duration of the offering period. Generally, an extended offering period tends to intensify the dilution, as employees are more likely to acquire shares at a significant discount. Assuming an initial fair market value of $30 on the grant date, with a 15% discount, the purchase price would be $25.50 (85% of $30). Over a 24-month period, if the stock's fair market value rises to $48, allowing employees to purchase shares at the discounted rate of $25 results in a 47% discount from the value at the time of purchase. Plans that incorporate provisions enabling automatic transition into a new offering period during a decline in the company's stock value exacerbate the dilutive effect.

ESPPs typically allow employees to acquire shares at the conclusion of an offering period, which commonly spans 3 to 27 months. Offering periods often adhere to increments of 6 months or multiples thereof, such as 12 or 24 months. Plans extending beyond 6 months often incorporate interim purchase periods. For example, in a 24-month offering period, employees might have the opportunity to purchase shares at the end of each of the four 6-month intervals. In such scenarios, the purchase price for a single period is typically based on the fair market value on the first day of the offering period or the last day of the purchase period, whichever is lower. The administration of plans with periods longer than 6 months can be more complex due to overlapping offering periods, where, for instance, a new 24-month offering begins every 6 months.

Some ESPPs incorporate a reset provision, often featuring offering periods of 12 or 24 months that commence every 6 months. For instance, in a 24-month offering period, there might be four purchase periods, occurring every 6 months. With a reset provision, if the company's stock experiences a decline in value, employees are automatically considered to have withdrawn from the current offering period at the end of the purchase period. Subsequently, they are enrolled in the next 24-month offering period. This automatic transition provides employees with the advantage of securing the lowest purchase price, as it is reset at the commencement of the new offering period.

Certain plans adopt 12- or 24-month offering periods without interim purchases or impose restrictions on the transferability of purchased shares. These restrictions prevent employees from immediately selling their acquired shares, aiming to encourage greater stock ownership.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) imposes a limit on stock purchases under an ESPP, capping it at $25,000 worth of stock in any given calendar year, with the value determined on the first day of the offering period. For example, in a plan with a 12-month offering period starting each January 1 and a stock value of $10 on that date, no employee may purchase more than 2,500 shares (adding up to the $25,000 limit) in that offering period. In cases where the offering period spans multiple calendar years, the limit remains at $25,000 worth of stock for each year of the offering period. While no statutory limit restricts employee contributions beyond this, many plans set a fixed percentage limit, typically ranging from 10% to 15%. For the majority of employees, this limit often falls below the $25,000 statutory threshold.

Closely tied to the aforementioned limitations is the ESPP's definition of compensation. While base pay is the straightforward choice, alternative definitions may be employed if base pay does not accurately represent the composition of an employee's overall compensation.

All employees are generally eligible to participate in an ESPP. However, Code Section 423 allows plans to exclude employees who have been with the sponsoring company for less than 2 years, work fewer than 20 hours per week, or are employed for less than 5 months per year. Additionally, individuals owning 5% or more of the company's common stock are ineligible to participate. While many companies have minimal or no service requirements, some may stipulate a brief employment period, such as three months, for participation. It's crucial to evaluate any service requirement in consideration of factors like employee turnover, industry norms, and the eligibility criteria of other benefit plans.

Offering periods typically initiate every 6 months, as previously mentioned. Consequently, new hires might encounter a waiting period of up to six months before being eligible to participate in the program, in addition to any existing service requirement.

Beyond the $25,000 limit mentioned earlier, most plans establish an additional cap on the number of shares an individual employee can purchase during a specific offering period. This addresses a loose IRS requirement applicable when the quantity of shares to be purchased is unknown until the final date of the offering period. The IRS stipulates that a plan must define a maximum cap at the offering periods outset. Typically, plans establish this cap through a formula or a specified number of shares.

Contributions made by employees to the plan become part of the employer's general assets. If an employee terminates their employment, the contributed money is typically refunded without interest. While few employers provide interest in such cases, those who do often offer a nominal rate, such as 5%.

Federal Tax Considerations

Once all the prerequisites outlined in the preceding sections are met, the federal income tax treatment of ESPP activity unfolds in the following manner:

The issuance of the option to employees is not subject to taxation.

The acquisition of shares by employees remains non-taxable, irrespective of the stock being readily tradable and having a value set at least 15% higher than the purchase price at the exercise date.

Unlike incentive stock options (ISOs) governed by IRC Section 422, the excess of the fair market value (FMV) of ESPP shares over the employee's purchase amount is not considered an alternative minimum tax (AMT) preference item.

The IRS stance is that while the excess FMV of ESPP shares over the employee's payment is exempt from income taxation, it is subject to FICA (Social Security) and FUTA (Unemployment) taxes.

Similar to ISOs, with the exception of a disqualifying disposition, the employer does not qualify for a federal income tax deduction for an employee's acquisition of ESPP shares, even if the employee benefits from a 15% discount.

IRS Section 423(c) introduces a special rule: in the event of a qualifying disposition of stock obtained through an ESPP (meeting the "two years from offering commencement date/one year from purchase date" holding period requirements), the employee is taxed at ordinary income rates at the time of disposition.

The taxable amount in a qualifying disposition is determined by comparing two values: the fair market value (FMV) of the stock at the offering commencement date over the purchase price (limited to the 15% discount established at the offering period commencement date) and the gain realized by the employee upon selling the stock. Simply put, if the stock is sold in accordance with the ESPP's holding period requirements, the IRS assesses the FMV of the stock at the offering commencement date against the option price (purchase price based on the FMV at the offering commencement date). This figure is then compared to the actual earnings when the stock is sold. The lesser of these two amounts is recognized as ordinary income to the employee, and any remaining gain is treated as capital gain, specifically long term. (To qualify as a disposition, the employee must adhere to the "two-years-from-commencement/one-year-from-purchase" ESPP holding period requirement.)

For the calculation of ordinary income in a qualifying disposition, the IRS utilizes the FMV of the shares at the offering commencement date. This remains true even if the value declined between the commencement date and the purchase date, resulting in the employee paying 85% of the lower purchase date FMV and effectively receiving a smaller actual discount amount.

The sponsoring employer does not qualify for a deduction on any part of the amount realized by the employee in a qualifying disposition, including the aforementioned ordinary income amount.

In the case of a disqualifying disposition (if the shares do not meet the commencement/purchase date requirements as previously detailed), the employee incurs ordinary income equal to the excess of the FMV of the shares over the cost to the employee.

Any surplus in the total amount received by employees upon their final sale of shares over the calculated ordinary income amount is categorized as capital gain, with its designation as either long- or short-term contingent upon the duration for which the employee held the shares after purchase, in accordance with the ESPP program provisions.

It's noteworthy that the calculations for qualifying and disqualifying dispositions employ distinct methods. In a qualifying disposition, the ordinary income amount is determined as the lesser of the discount percentage (e.g., 15%) multiplied by the offering commencement date fair market value (FMV) purchase, or the actual gain realized from the stock's sale. The offering date FMV is used for this computation, even if the stock's FMV decreased between the offering commencement date and the purchase date, and the shares are effectively purchased at the lower date FMV (minus the discount).

Conversely, in a disqualifying disposition, the ordinary income amount is computed as the excess of the stock's FMV at the purchase date over the amount paid by the employee. This amount will not be lower than the offering commencement date FMV of the shares (multiplied by the discount percentage), but it might be higher if the stock's FMV increased between the offering commencement and purchase date.

It's crucial to note that the employee's actual gains on the sale of shares are inconsequential to this calculation in a disqualifying disposition. In this context, in a disqualifying disposition of ESPP stock, the employee recognizes ordinary income equivalent to the excess of the stock's FMV at the purchase date over the amount paid by the employee for the shares on the purchase date. This holds true even if, after the purchase date and before the employee's sale of the shares, the FMV declined such that the employee's actual gain was less than the spread at the purchase date.

The rule governing the determination of the taxable amount in a disqualifying disposition of ESPP stock differs from the rule applicable to ISO disqualifying dispositions. In the case of ISOs, the employee's ordinary income is confined to the gain realized upon the disposition of the shares. In other words, if the employee's gain on an ISO disqualifying disposition is less than the spread at the ISO's exercise, the employee's ordinary income equals the gain at the disposition of the shares.

It's essential to highlight that in the context of ESPP disqualifying dispositions, the employee's ordinary income (or former employee's, as the case may be) is always equivalent to the excess of the actual fair market value (FMV) of the shares at the purchase date over the price paid at the purchase date. This holds true regardless of whether the discounted price is tied to the shares' FMV at the period commencement date or the purchase date. Moreover, it remains consistent irrespective of whether the calculated ordinary income amount exceeds the employee's gain on the ultimate disposition.

For an employer to be eligible for a deduction related to an employee's disqualifying disposition, the employer must:

Establish an administrative system, such as requiring that any sales, until the expiration of the ESPP holding period, be conducted through a captive broker or implementing a system of employee and former employee self-reporting to capture disqualifying disposition information.

Report the amount of ordinary income realized by the employee (or former employee) on the disqualifying disposition on an IRS Form W-2 or a 1099-MISC.

It's worth noting that the data collected by the sponsoring employer for reporting purposes under Section 6039 of the IRC, as discussed later, might be insufficient. This is due to the fact that the first transfer by the employee—potentially the last transfer requiring the employer to collect information—may involve transferring the shares to the employee's own broker in street name, potentially not constituting a true disposition, whether disqualifying or otherwise.

Section 6039 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) mandates that employers offering Employee Stock Purchase Plans (ESPPs) must provide employees with an annual notice regarding their ESPP activity for the preceding year on or before January 31.

For publicly traded companies, shares issued under an ESPP are typically registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) using Form S-8. The registration process through Form S-8 is relatively straightforward and comprises two components: a prospectus and an information statement. The prospectus is designed for distribution to employees but is not filed with the SEC. On the other hand, the information statement, which must be filed with the SEC, primarily consists of documentation such as annual financial reports that the company has prepared for other purposes and is incorporated in the S-8 by reference.

Due to amendments made to Rule 16b-3 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 in 1996, transactions related to ESPPs (excluding sales of purchased shares) are exempt from Section 16(b) of the Exchange Act, which governs short-swing profit rules. Additionally, transactions under any ESPP are exempt from the reporting requirements of Section 16(a).

Financial Accounting

Employee Stock Purchase Plans (ESPPs) and other broad-based stock purchase plans can avoid an earnings charge if they meet specific criteria.

To qualify for the exemption from an earnings charge, a plan must possess the following characteristics:

It must be subject to certain minimum service requirements.

Stock must be offered to all eligible employees, either equally or based on a uniform percentage of pay, and a substantial majority of full-time employees must be eligible.

The purchase period must be of a reasonable duration.

The purchase price discount must not exceed what is considered a reasonable offer to shareholders or others.

FASB Interpretation No. 44 (FIN 44) stipulates that a discount of up to 15% from the fair market value (FMV) at the offering period commencement date is generally deemed reasonable. Additionally, a discount equal to either 15% of FMV at the commencement date or the FMV at the purchase date will be considered reasonable for an ESPP, specifically a plan that qualifies under IRC Section 423.

Equity in Pension Plans

This section delves into the integration of company equity into pension plans, a concept that has evolved significantly in response to various factors, including changes in financial accounting guidelines, the provisions of the Pension Protection Act of 2006, and fluctuations in stock market indices over the past decade. The dynamic landscape has presented challenges for many plan sponsors, particularly those facing liquidity constraints and competing cash needs, leading them to explore the utilization of company stock contributions as a strategic resource for pension plan funding.

The contribution of company stock to pension plans is a nuanced process governed by ERISA regulations and the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). Plan sponsors may, in certain cases, require a prohibited transaction exemption from the Department of Labor before incorporating company stock into the pension plan.

Before delving into the feasibility of funding pension plans with company stock, it is crucial to comprehend the minimum funding rules introduced by the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA), which amended the pre-existing minimum funding standards under ERISA and the Internal Revenue Code. The PPA mandated that sponsoring companies achieve full funding of their pension plans over a seven-year period, commencing in 2008. This entailed a minimum annual contribution, calculated as the present value of benefits earned in each plan year, plus the amount necessary to amortize funding shortfalls over the stipulated seven-year period. Additionally, the PPA established a funding target of 100%, requiring each plan to be funded at an amount equivalent to the present value of all accrued and earned benefits as of the beginning of the plan year. Plans deemed at-risk were assigned even higher funding targets based on actuarial funding assumptions. These stringent funding standards have prompted many sponsoring companies to reassess their strategic approach to pension plans, with some opting to freeze or dismantle their defined benefit pension plans in response.

The inclusion of company stock as a contribution to a pension plan is treated as a transaction akin to the sale of company stock to the pension plan. A critical prerequisite is obtaining the concurrence of the plan's trustee, who must endorse the alternative infusion of company stock as a valid funding mechanism. This endorsement is a fundamental fiduciary responsibility. Additionally, the plan's fiduciary must assess and determine the value of the stock contribution to steer clear of engaging in nonexempt prohibited transactions, marking the valuation process as a pivotal event.

The stock valuation involves consideration of various factors, including:

Determining the appropriate discount to incorporate into the valuation to account for the inherent lack of liquidity associated with a stock contribution.

Evaluating the limited tradability of the contributed stock.

Assessing the company's perception of its stock value relative to its current market price. If the stock is perceived as undervalued, the investment may yield higher returns. However, if the company is currently associated with substantial risks, the stock may face challenges, potentially negatively impacting the pension plans. This nuanced evaluation is crucial for making informed decisions regarding the integration of company stock into the pension plan and requires a thoughtful and comprehensive approach to fiduciary responsibilities.

Legal Considerations for Stock Contribution to Pension Plans

ERISA (Employee Retirement Income Security Act) prohibits employer stock holdings in benefit plans unless designated as qualifying employer securities. Specifically, concerning pension plans, these securities encompass stock of the plan sponsor, subject to the following conditions:

The pension plan cannot hold more than 25% of the outstanding shares of the sponsoring company at the time of the stock contribution to the pension plan.

At least 50% of the issued and outstanding shares must be held by parties fully independent from the plan sponsor.

Both ERISA and the IRC (Internal Revenue Code) explicitly forbid certain transactions between an employee benefit plan and the plan sponsor. Consequently, any contribution of company stock to a pension plan is categorized as a prohibited transaction. Nevertheless, exemptions exist under certain conditions. To qualify for these exemptions:

The plan's acquisition of employer securities must be made based on adequate consideration.

No commission can be charged for the transaction.

The 10% rule, which prohibits the use of plan assets to acquire employer securities exceeding 10% of the total plan assets, must not be violated.